Who Is the ‘I’ in All of This?

Learning About Myself Through Self-Study

Context of Study

…thinking about you as a collaborator, partly what I love is the ability and the freedom to go on these circular journeys that come back to the point (Participant A).

Self-study. The name says it all, doesn’t it? Or does it? Self-study is the study of the self in action, by the self, through the self (and others, of course). As Jason Ritter and Oren Ergas (2021, p.1) point out “Studying oneself is not new. Well over 2000 years ago Socrates expressed the view that an unexamined life is not worth living, while the Buddha similarly stressed how it is important to be a lamp unto yourself.”

Self-study methodology places the self at the centre of the research endeavour. Vicki Kubler LaBoskey (2004, p. 826) reminds us that, “Self is central, and that means the whole of the self – past and present, emotional and cognitive, mind and body.” As self-study researchers, we have to grapple with the self, in order to understand our practice. However, this is not an easy or comfortable task; it asks us to confront our self/selves in ways that are challenging, demanding a high degree of self-reflection. It strikes me that much of self-study is often directed toward understanding the self through interaction with participants, sometimes to the exclusion of the inward gaze on the self. This may be in response to the all-too-common accusation of navel-gazing that is levelled at self-study (Ovens & Fletcher, 2014, p. 8), but an essential part of the process of self-study for me is coming to knowing the self better through the inward gaze. That process, as explored in my doctoral study, is my focus in this paper.

In line with the self-study imperative to share and make public our insights and new learnings (Kubler-LaBoskey, 2004; Samaras, 2011), this paper elucidates how I sought to deepen my understanding of my 'being' self, in my larger study. It is also, however, and more recently, motivated by my own response to Jason Ritter and Oren Ergas’ fascinating work regarding the place of the self in self-study (Ritter & Ergas, 2021; Ergas & Ritter, 2021), which has prompted me to go back to my earlier study to consider the ways in which I gazed inward (to appropriate Ergas & Ritter’s term) in my own work.

In my self-study doctoral project I examined my own collaborative, creative practice as a South African theatre-maker and university educator (van der Walt, 2018). In doing so, I sought to gain a greater understanding of how the forces of creative collaboration played out in my work with my two key collaborators and critical friends, and the students with whom we work. I wanted to discover the personal qualities, values, ontological and ideological positions, and ways of thinking that I bring to the process of collaborative theatre-making, to uncover who I am in my practice. This lies at the heart of my quest to understand what I would term my being self, which encapsulates all of the aspects listed above, as opposed simply to my doing self, which is more focused on my actions in the world. Excavating the inner workings of my own practice, exploring what makes my collaborative practice work, and what I bring to my practice in terms of knowledge, attitude, and expertise, allowed me to uncover that being self more fully.

Aims

In this paper, I use the notion of the being self and the doing self to distinguish between two foci: inward and outward. Obviously both matter in self-study, but the inward-looking, being aspect of our engagement with self is often marginalised, partly because of the challenge of how to know that self. What I offer here is a methodological exemplar (Mishler, 1990) of an approach to meeting that challenge, allowing us as self-study researchers to position the self unashamedly at the centre of the research endeavour, and “make self-study more self-focused as opposed to merely self-initiated” (Ritter & Ergas, 2021, p.11).

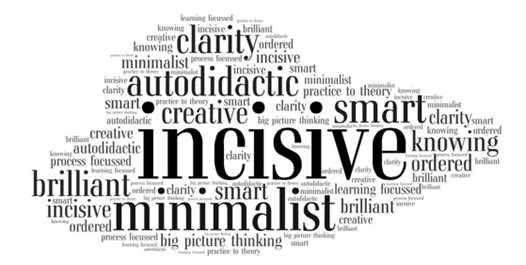

The paper thus offers one answer to the challenge of how to know the self in self-study, by demonstrating a methodological approach that uncovers the being self, rather than just the doing self, and which foregrounds the being self (which is essentially private), in a public and researchable way. In so doing, I also seek to show how graphic representations such as word clouds and concept maps can help to highlight and reframe data generated through interviews, making the hidden self tangible and material. These processes facilitate self-reflection and an understanding of how who I am affects what I do in my practice as a self-study researcher.

Method(s)

In my discussion here, I am not seeking to re-analyse the data from my doctoral study, but rather to offer a meta-analysis of the results of my initial analysis, using my earlier work as an example of an approach that grapples with the being self. Thus, I am able to re-examine and re-interrogate my earlier study in a new way. Before doing so, however, it is important to understand how that data was generated.

In order to learn more about my creative, collaborative, being self/selves in my initial study, I drew on:

- data generated through interviews with both of my collaborators, who are also critical friends (Participants A & B);

- data generated through interviews with former students who were involved in my theatre-making project (Participants C, D, E, F & G), conducted after the completion of the project.

- my Reciprocal Self Interview (RSI) (Meskin et al., 2014), in which I was interviewed by my critical friend, using a schedule of questions that I had drawn up myself. This process allowed for deep introspection and self-reflexive engagement.

Each of these interviews was recorded, and then professionally transcribed. Initially, I read these transcripts as I would any play text, seeking the subtext and the hidden meanings embedded in the dialogue. Having done this and gained a broad overview, I examined the data repeatedly, in a recursive, hermeneutic process of “making meaning of [my] data'' (Samaras, 2011, p. 198), looking for repeated ideas, key words, and themes, and common phrases.

In analysing these data sources in my initial study I looked closely at the ways in which my collaborators in particular had answered my questions. I did not provide specific descriptors for my self; rather, I asked each of them directly to characterise me as a collaborator and describe what it is like to collaborate with me. Their answers provided me with a list of descriptive phrases and adjectives that they would use to describe who I am as a collaborator. I was also able to glean a number of other descriptive words and phrases from my interviews with student participants. I first created a rough list of these and then used concept mapping (see Van der Walt, 2020) to code these, grouping the words and phrases thematically.

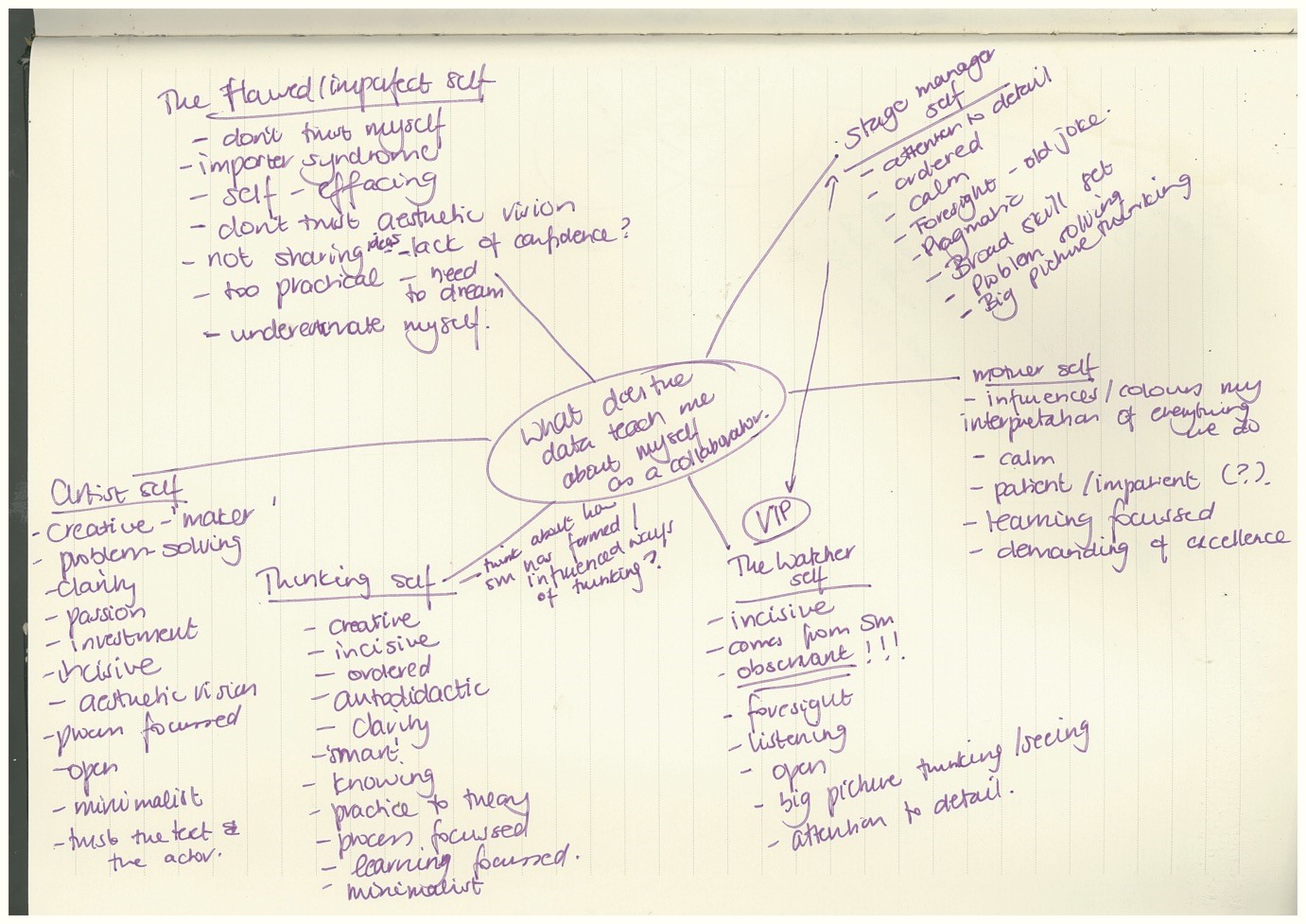

Figure 1

A Concept Map of the Ways in Which My Respondents Described Me As a Collaborator

I then compared these to the insights I had gained through my RSI, to understand the points of connection, overlap, and difference in the way I perceived my self, as opposed to how others saw me. This use of a range of sources and perspectives allowed me to 'crystallize' (Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005) my understanding of my self/selves as a creative collaborator. In so doing, I was able to identify six different 'selves', and generate a word-cloud formation for each of them, using the lists of words and phrases in my concept map.

Outcomes: Finding My Being Self

What this process of analysis and meaning-making revealed to me was that I can conceive of a series of selves that are me as a creative collaborator: the Stage Manager self, the Mother self, the Watcher self, the Thinking self, the Artist self, and the Flawed self. I have chosen here to present a general, summative discussion of each of these selves, showing how the ways in which I have been described by others helped me to understand myself.

1. The Stage Manager Self

So much of what I think and do as a theatre-maker, and as a researcher, is because I was a Stage Manager first. The practical stage skills, the interpersonal communication skills, and the organisational skills that I developed while working as a Stage Manager have all continued to be the basis of my practice. I believe that a large part of why I am a collaborator is because Stage Managers have to be good at working with others, as they are the one person in any theatrical production who has to interact and communicate with every artist and technician. The Stage Manager sits at the centre of the spider web that is the production, connecting all the disparate parts, and this has influenced the way that I work in collaboration with others.

In my RSI, my critical friend challenged me to think about the skills and ways of thinking that I have carried over from being a Stage Manager, into my directing and theatre-making practice. My response reveals a deep understanding that my years as a Stage Manager have made me the director and theatre-maker I am today:

I think that a Stage Manager has to be able to listen, hard. They have to be very observant because they have to pick up on things …. it is that sense of anticipating the problem before it arises, and fixing it…I think that does affect how I direct, in that I will see the problem coming before it has even got there….

Thus, Stage Management has taught me to be a pragmatic, listening, observant director, who is able to foresee problems before they arise.

When I analysed the ways in which my collaborators described me, many of the skills and attributes they identified had developed as a result of my Stage-Management experience. These included my high level of attention to detail, my ordered and calm approach (if the Stage Manager in a production panics, disaster is surely imminent!), my broad theatrical and stage skills, my ability to problem-solve and foresee problems before they happen (as the old joke goes, “How many Stage Managers does it take to screw in a light…. oh, it’s already done”), and my ability to see the big picture of a production, and to consider all the moving parts of a theatrical performance, can all be linked back directly to my experience as a Stage Manager.

2. The Mother Self

At a research seminar years ago, a colleague asked me to think about the ways in which my being a mother influences and changes what I do as a practitioner and researcher. At the time, I was struck by her question but really did not know how to answer it. I do not think that I am particularly motherly in relation to my students and my work, and there was, at first, no obvious response to her question.

However, while looking at the data, it became apparent to me that the reality that I am a mother influences what I do and who I am as a collaborator. As I explored the interviews, I noticed that I came back repeatedly to the idea of how having children affected my work. On a practical level, of course, having them means that I cannot simply go off and rehearse every evening or every weekend. My theatre-making and research work has to fit in around the needs of two boys with busy lives, who need me more than the production, the project, my collaborators, or my students ever will. Being a mother has meant that over the years, my ability to completely submerge myself into a theatrical or research project has been increasingly curtailed. Despite this, and even though I consciously try not to take a mothering role with my students and cast members, they felt that I had a very patient and caring approach. Participant C commented on this, saying:

Oh you’re very patient with us. … the fact that you could actually sit there and devote even two extra minutes to a performer who needed a little bit of extra help was awesome.

While I would characterise myself as very impatient at times, the student’s response indicates a more nurturing perspective in the time available.

Another aspect of my work that reflects my Mother self is the fact that I am, as Participant B put it, “incredibly focused on learning.” To me, it is imperative that students learn from the process of collaborative theatre-making, and this focus on learning and on the development of the students is related to my mothering instincts. Like any parent, I want the best for the children in my care, and this feeling extends to the students for whose learning I am responsible. Like any parent, I can be demanding of excellence; I challenge my students because I fully believe it to be in their best interest, and that by expecting more of them, I am making it possible for them to grow and develop.

3. The Watcher Self

Early in my process of interrogating my practice as a collaborative theatre-maker, I examined rehearsal photographs and videos which revealed something that I was only aware of on an unconscious level; while the photographs and videos consistently show my collaborators working at the front of the stage, actively engaged with the students and what they are doing, in many cases, I am not pictured with them, simply because I am sitting up in the auditorium, watching what is happening. This really struck me; initially, I thought I seemed too distanced and removed from the process, that I was somehow less involved than my collaborators in the making of the work. However, in my RSI I had a revelation:

I didn’t study directing as such. … I know how to do it because I was a stage manager…I learnt how to direct by observation. And I think observation is very important in my process …. I sit and watch …, and for a long time I thought ‘you are being too passive’ but I have realised that it isn't about passivity. It is about observation.

I realised that what I had initially perceived as a weakness in my work, was just a different way of approaching the work. As Participant A noted, “the broad stroke is clear to you”; because I tend to sit back and look at the bigger picture of what is happening on the stage, I am able to see the whole of the canvas of what we are trying to achieve.

My collaborators both characterised me as observant and incisive. To me, these two things go hand in hand; because I am a watcher, I work through careful observation, and equally focused listening, to see to the heart of a problem or an issue. Participant A described this aspect of my practice as being “able to cut through stuff and go ‘there’s the problem’. It’s being able to manage the orderliness of it with ease.” As a result of my close observation and careful listening (which I believe go hand in hand), I am able to pay close attention to detail, while also being able to foresee problems before they happen.

This ability to observe also extends to life outside of the rehearsal room. I am not only a watcher in the creative theatre-making process, but also in life. When I interviewed Participant A, I observed that “to be a good director, you have to be a good observer of life, because you have to have observed human behaviour.” This is important to me; I have come to understand that this quality of observation and incisiveness, rather than being a weakness in my work, is probably my greatest strength.

4. The Thinking Self

In considering my Watcher self, and my critical friend’s questions about what ways of thinking I have carried over from Stage Management, I examined the types of thinking that I bring to my collaborative theatre-making practice. All my theatre work is an enactment of my thinking, brought to life on the stage. Thus, the ways in which I think, and the types of thinking that I bring to the process determine, to a large extent, the type of theatre that I make.

My collaborators characterised me as a creative, incisive thinker. I am ordered in my approach, and this counterbalances Participant A’s own admission that she is “not very good at order”. Because of this, I am able to create clarity out of moments of apparent chaos. In many ways, I am something of a minimalist; I tend to remove the noise to simplify a concept or an idea, in the pursuit of clarity.

Participant A characterised both of us as “smart” in her assessment of me. I think she meant that we both have a wide range of knowings that we are able to bring to the work. She explained, “I think, because we read, because we engage with the world, I think we’re interested in the world, so we bring [that] to it.” This sense of value in what I know and what I think is an important part of the Thinking self that I bring to the process of collaborative theatre-making.

Participant B saw me as process-focused and learning-focused. Because the students’ learning is important to me, I am very focused on the process of what we are doing, rather than on the product. While the quality of the finished theatrical work is important, to me, the learning that happens within that process is more important. Linked to this is the fact that I tend to think from practice to theory; I work practically and instinctively, and then later use theory to understand what we have done and why we did it.

5. The Artist Self

At the heart of my practice lies the fact that I am making a work of art. Thus, my creative, artistic self is a crucial part of who I am as a collaborator. I am a maker of all sorts of things; I spend a lot of time knitting or sewing, or engaging in other crafts. The fact that I make things is integral to who I am, and offers me an enormous amount of pleasure. These acts of making are all, in a way, attempts to solve a problem of one sort or another. In trying to solve the problems inherent in making a shawl, or in directing a play, or writing a research paper, I am focused on the process, rather than the product.

My sense of myself as an artist is, of course, deeply tied up with my Thinking self. The qualities of clarity and incisiveness that I identified as part of my ways of thinking are also an important part of my ways of making as a creative person. I have a fairly strong sense of aesthetic vision, and I bring this to bear upon my work in numerous ways. Because I am open to new ideas and concepts, I am able to bring these to the art that I make, to enrich the work that I do.

When asked to characterise me as a collaborator, Participant B said:

What overrides are the ideas of creativity and learning, and you know what, passion! The absolute whole embodied engagement in what you’re doing with the students, with the show, the thematic content, with everything. And investment: If you’re in something, you’re invested in that.

This sums up so much of my artistic approach: if I am involved in making a theatrical work, I bring to it a sense of investment and passion. I am completely engaged with what I am doing, and bring to bear all that I have in my arsenal of skills, in the making of a new work.

6. The Flawed Self

Of course, no one is perfect, and while I identified a number of strengths that I bring to my creative, collaborative work, the data also helped me to examine the weaknesses in my approach. I have chosen to call this the Flawed self, to convey the ways in which my self can have a negative effect on my work.

The biggest flaw that my collaborators identified is my tendency not to trust myself and my own judgment, in the theatre-making process. I underestimate my own contribution to what we are doing. Participant A observed, “I don’t think you trust yourself enough.” This links back to a sense of imposter syndrome (Clance & Imes, 1978); despite all my years of working in the theatre, and all my experience, I am still sometimes crippled by the thought that I don’t actually know what I am doing.

This is also reflected in the fact that I tend to be very self-effacing. Participant A again characterised this when she commented that, “I sometimes think that you are not assertive enough; you allow yourself to be not assertive, if that makes sense. Like you take a backwards step.” This sense of “stepping back” from the work reflects in the fact that my collaborators felt that I sometimes don’t share my ideas freely enough; I am, at times, content to just go with their ideas, rather than fight for my own.

Conclusion

In considering what I have learned about my creative, collaborative, being self/selves, through self-study, I am able to conclude that the selves that I have identified through my examination of the data – the Stage Manager self, the Mother self, the Watcher self, the Thinking self, the Artist self, and the Flawed self – all co-exist and overlap within my practice. I am not any one of these things on their own; rather, my practice is an enactment of all of these selves simultaneously.

In conceiving of a series of selves that are me as a creative collaborator, I also show how the ways in which I have been described by others have helped me to understand my self in my own study; an understanding of myself as the ‘Watcher self’ allows me to use my powers of observation more effectively in my work, instead of seeing them as a weakness; an understanding of myself as the ‘Flawed self’ allows me to consider the ways in which I can be more assertive about my ideas, bringing greater confidence in myself to my practice. In this process of coming to know about my being self/selves, I embrace Sandra Weber’s notion that “Self-knowledge is power; sharing self-knowledge is empowering” (Weber, 2014, p. 17), and so in developing a deeper understanding of my being self and my practice, I am more empowered to use that practice in meaningful ways.

In particular, my analysis of these various aspects of my self/selves has led me to a more complex understanding of the “I” in my self-study, as a multi-faceted, complex, doing entity, which is fundamentally connected to the complexity of being that underpins all of the selves that I inhabit in my work. Thus, my understanding of both my doing and my being self is expanded through the inward gaze of my research endeavour. Developing graphic representations such as concept maps and word clouds of the multiple aspects of self I had excavated, allowed me to navigate the complexities and interactions within and between my selves. By focusing on the data using the lens of who as opposed to what, it is possible to engage more deeply with what underlies actions, behaviours, and thought processes, and what these reveal about the being self. While I only discuss one method for investigating the being self, what is crucial, for me, is the determination to do so. By focusing on the who (vs. the what), we can explore the self in multiple ways, deepening insights and offering new possible perspectives and interpretive insights, framing the self-study project in a more holistic and (potentially) probing way.

References

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The impostor phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice, 15(3), 241-247.

Ergas, O. & Ritter, J. K. (2021). Expanding the place of the self in self-study through an autoethnography of discontents. Studying Teacher Education, 17: 1, 4-21, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2020.1836486.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817-869). Springer.

Meskin, T., Singh, L., & van der Walt, T. (2014). Putting the self in the hot seat: Enacting reflexivity through dramatic strategies. Educational Research for Social Change (ERSC), 3(2), 5-20.

Mishler, E. G. (1990). Validation in inquiry-guided research: The role of exemplars in narrative studies. Harvard Educational Review, 60(4), 415-442.

Ovens, A., & Fletcher, T. (2014). Doing self-study: The art of turning inquiry on yourself. In Ovens, A., & Fletcher, T. (Eds). Self-study in physical education: Exploring the interplay between scholarship and practice (pp. 3-14). Springer.

Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.) The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 959-978). Sage Publications Inc.

Ritter, J. K. & Ergas, O. (2021). Being a fish inside and outside the waters of self-study. Professional Development in Education. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1902841.

Samaras, A. P. (2011). Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry. Sage Publications Inc.

van der Walt, T. (2018). Co-directing, co-creating, collaborating: A self-reflexive study of my collaborative theatre-making practice. [Doctoral Dissertation. University of KwaZulu-Natal]. UKZN ResearchSpace. https://researchspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/17872.

van der Walt, T. (2020). ‘Show, don’t tell’: Using visual mapping to chart emergent thinking in self-reflexive research. Journal of Education. Special Issue. Methodological inventiveness in self-reflexive educational research. 78. 76-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i78a05

Weber, S. (2014). Arts-based self-study: Documenting the ripple effect. Perspectives in education. Special Issue. Self-study of educational practice: Re-imagining our pedagogies, 32(2), 8-20.