Testimonio Pedagogy on the Borderlands in Teacher Education

Breaking Open Spaces to Let the Light In

Introduction

Pedagogy on the borderlands means sharing classrooms with hungry ghosts…In my graduate studies [classrooms]…I find myself pointing to the ground. “You’re living in the colonies…This land has been covered in blood for hundreds of years…This is where our classrooms rest[”]…I hope for a pedagogy on the borderlands that can house the irrational, the angry, the tears, alongside the philosophical and analytical…dealing with hungry ghosts requires nothing short of every source of knowledge we possess. [It]… is a place of possibility…where our diverse, hybrid bodies, and the generations of “warring ancestors” inside them, sit in rooms together and might just deal with the dead... (Pendleton Jiménez, 2006, pp. 225-226).

New Mexico bears a unique history wherein Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache Peoples have, since time immemorial, been stewards of the land and are its intergenerational inheritors. Since 16th century European conquest, the histories of Indigenous[1] and Mexican/Mexican American groups have intersected, merged, diverged, and clashed with Spanish conquistadores and colonists and their subsequent descendants, Nuevomexicana/os and Mexicana/os[2]. But while Indigenous and Nuevomexicana/o communities date back millennia and nearly five centuries respectively, their land, languages, lifeways, histories, and spiritualities have been stolen/co-opted, silenced, invalidated, and targeted for erasure, and their children mentally, spiritually, and physically harmed by public schooling (Blum Martínez & López, 2020; Gonzales-Berry & Maciel, 2003; Lomawaima & McCarty, 2006; Martinez, 2010; Suina, 1985). Today, people of color comprise the numerical majority (U.S. Census, 2019); in K-12 district schools, 76% of students are people of color including 61% Hispanic, 10% Indigenous, 2% Black, and 1% Asian (New Mexico Voices for Children, 2020). Despite their numerical majority status, people of color in New Mexico struggle to find economic, social, and educational justice. Today, New Mexico ranks 50th overall in child wellness (New Mexico Voices for Children, 2020), a statistic disproportionately impacting low-income communities of color. The courts have also documented sociopolitical inequities. In 2018, the New Mexico Supreme Court found the State failed its constitutional mandate to equitably educate Indigenous children, English learners, children with disabilities, and socioeconomically disadvantaged children (nmpovertylaw.org). While this ruling was contextualized within New Mexico’s K-12 education, it has implications for educational transformation at all levels. Within histories of educational and social injustice, education students are not simply those who will one day serve future students—they are also among those who have been impacted.

This chapter highlights the self-study in teacher education project we engaged in one required licensure course to better serve our own (under)graduate students of color, those with disabilities, and our multinational, multilingual students who have likewise been shaped amid the struggle for educational justice. We highlight that the educational, economic, mental, emotional, and physical health that students in higher education work to maintain within an often unwell system has been further harmed by the COVID-19 pandemic which has exacerbated social isolation and disenfranchisement. For teacher preparation students and educators, building a hopeful, humane, socially just pedagogy in the borderlands (Delgado Bernal, 2006; Pendleton Jiménez, 2006) means recognizing that higher education pedagogy must not only heal wounds of U.S. schooling as colonization in New Mexico (Blum Martínez & López, 2020; Gonzales-Berry & Maciel, 2003; Martinez, 2010; Sosa-Provencio & Sánchez, 2020; Suina, 1985); it also must bring students and educators together across difference and distance to foster our shared humanity and create learning spaces that are loving, challenging, critical, and life-giving (Hamilton, 2021).

Background of Our Self-Study: Fall 2015 - 2020

Nationally, over 80% of pre-service and in-service educators are White and English-dominant (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020). While the makeup of the teacher education students at our Southwest institution is much more diverse (49.5% Hispanic, 5.4% Native American, 2.1% Black/African American, 1.3% Asian, and 36.7% White), program faculty navigate the fact that the dominant teacher preparation model—despite geography or demographics—is steeped in Eurocentric epistemologies (Blum Martínez & López, 2020; Rendón, 2009; Valenzuela, 2016). To contend with these realities, Mia, a bilingual Nuevomexicana teacher educator, worked to fashion a "pedagogy of possibility" (Delgado Bernal, 2006) by designing a required course into what came to be called the Testimonio Curriculum Lab. Together with high school youth, university students integrated the Latin American narrative genre Testimonio—first-person antiracist, womanist narratives unearthing critical consciousness and the resistance/resilience of especially Black and Indigenous Latina/o/x communities; Testimonio honors and integrates silenced intellectual legacies, languages, land connectedness, and embodied knowing across time and space (Latina Feminist Group, 2001; Menchú, 1984/1997). Course curriculum paired Testimonio with pedagogical framework expanding dominant notions of literacy to include multiple literacies ("multiliteracies") (Beach et al., 2010) to encapsulate the many ways that diverse youth make sense of and navigate multiple worlds. Between the fall of 2015 and spring of 2020, high school youth worked alongside undergraduate and graduate students to plan, teach, and evaluate student-centered, culturally relevant curricula. Through weekly lessons, youth highlighted their lived realities, schooling experiences, and visions for transformation through photography, original artwork, musical lyrics, memes, spoken word poetry, journal entries, photo collages, and excerpts of published Testimonios. Over time, their writings were anonymized, compiled, and set aside for future use.

Student-Centered Testimonio Inquiry in Teacher Education: Fall 2020

In the fall of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic prohibited our high school work and moved us online. In line with LaBoskey and Richert (2015) who assert the power of situating teachers to engage inquiry and self-reflection, Mia designed a student-centered inquiry project around the youth writing packets (which came to be called ‘data packets’) in order that she and her students—overwhelmingly multilingual students of color—could more deeply understand schooling experiences and multiliteracies of marginalized youth and how to build pedagogies for educational justice in future classrooms.

Our inquiry forged a space wherein pre-service students, including we three graduate student authors who were enrolled students and co-teachers, could engage our own knowing, embodied experiences, and curiosities as largely students of color to build something more hopeful and engaging than what the dominant model of schooling offered. It is this fall 2020 student-centered inquiry and our own practice as teacher educators therein that provide the context of our self-study.

Objectives

We utilize the arts-based self-study methodology "tapestry poetry" (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2022) to more deeply understand the capacity of student-centered Testimonio inquiry in teacher preparation. By centering our own difficult narratives of schooling at intersections of race, class, gender, language/dialect, citizenship, and geography, we were transformed as educators. This chapter conveys the Findings of one self-study conducted at a large R1 institution in the Southwest by one professor and three graduate students who led and participated in this inquiry. Our four-person research/writing group includes Mia, a Chicana/Nuevomexicana Associate Professor of teacher education; two doctoral students, Ybeth, a Mexicana female early childhood educator, and Jackie, a White female secondary educator; and Helena, a Mexicana female Master’s student studying antiracist literacy education.

We utilize the methodology of Self-Study in Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP) to more deeply understand and disseminate how—in our process of centering the knowledge and experience of undergraduate students who are themselves living and learning amid contested sociopolitical identities—we four shared our own complex identities and intergenerational knowledge. In so doing, we broke open a radical space of belonging for our students, ourselves, and our own generations and ways of being which converged around our working class, bilingual, White and Mexicana, and (future) teacher educator identities.

Theoretical Framework

We position research as a sacred undertaking wherein mind/body/spirit, land situatedness, and theoretical/methodological/epistemological framing live in reciprocal relationship to each other. We situate self-study within a decolonizing womanist-centered framework of Testimonio (Díaz Soto et al., 2009; Latina Feminist Group, 2001). Levins Morales’ (2001) work on Testimonio illuminates the symbiosis of knowledge, body, and land as homemade theory—organic material to which the earth still clings which is best fashioned out of our shared lives (p. 28). We not only work to unearth our own organic intellectual soil but likewise to expose and disentangle the colonial trappings of teaching and research conducted in marginalized communities. We utilize our theoretical framework to challenge and remember how we ourselves approach knowing—with attention to place, our positionalities, and the communities to whom our work belongs and serves now and in the future (Hamilton, 2021). To achieve theory that is embodied, justice-oriented, and feminist, we center the beauty and knowledge of our female generations and build upon the wisdom of our own marginalized communities. Through self-study, we aim to understand how we worked with students in the fall of 2020 to make theory “out of the stuff in our pockets, out of the stories, incidents, dreams, frustrations that were never acceptable anywhere else” (Levins Morales, 2001, p. 32) and the implications this has for teacher education.

Literature Review

According to Delgado Bernal (2006), the 'U.S. borderlands' is a geographic, emotional, and psychological space Indigenous and Mexican/Mexican Americans of blended Indigenous, African, and European ancestry have occupied for eons and centuries respectively even as they have been denigrated and cast as ‘foreign other’ by European and U.S. imperialism. Since the 1893 inception of U.S. public schooling and its contested institutionalization in New Mexico (1893-1910), it has been one of the most powerful weapons of colonization and imperialism, utilizing Eurocentric curriculum and pedagogies aimed at social reproduction, cultural erasure, and the silencing of diverse histories and knowing (Blum Martínez & López, 2020; Kliebard, 2004; Lomawaima & McCarty, 2006). Herein, Western frameworks of knowledge—including ontologies, epistemologies, and methodologies which undergird teaching, learning, and inquiry at all levels including higher education—are steeped in a Eurocentric cognitive imperialism that engages knowledge as "Other" and bears no reciprocal commitment to either the knowledge produced or the communities from which it emanates. Though Battiste and Henderson (2000) write the following to illuminate Indigenous students’ experience with cognitive imperialism, students of color across identities often likewise experience White dominant schooling as,

looking into a still lake and not seeing their reflections….They become alien in their own eyes, unable to recognize themselves in the reflections and shadows of the world. In the same way that Eurocentric thought stripped their grandparents and parents of their wealth and dignity, this realization strips modern Indigenous students of their heritage and identity. It gives them awareness of their annihilation (p. 88).

In order to disempower this emotional/psychological/physical detriment, especially for Indigenous, indigenous heritage Mexican/Mexican American students and all marginalized communities in this Southwest borderland, educators at all levels may adopt pedagogies of healing and possibility which center the identities and knowledge gained by those who navigate power and privilege while occupying multiple worlds (Delgado Bernal, 2006; Pendleton Jiménez, 2006). Adopting a "pedagogy on the borderlands" across educational institutions and particularly in higher education taps into the knowledge centers of those who straddle the space between nations, racialized identities, languages, sexualities, and spiritualities. A pedagogy on the borderlands accesses the wisdom of the diverse Peoples, including, “subtle acts of resistance…negotiating, struggling, or embracing their bilingualism, biculturalism, commitment to communities, and spiritualities” (Delgado Bernal, 2006, p. 115). Within underserved communities in particular, educators must invite students to bring their whole selves into the classroom—to disempower Eurocentric frameworks and forge belonging for the multitudinous nature of their being-ness. So doing disrupts, “neat separations between cultures…[by] tearing apart and then rebuilding the place itself. The border is a locus of resistance, of rupture, of implosion and explosion [formed by] putting together the fragments and creating a new assemblage” (Anzaldúa, 2015, p. 49). One approach to this healing, resistant, affirming, and collective pedagogy on the borderlands is Testimonio.

Testimonio narrative originated in Latin America's African, Indigenous, and female struggles against erasure and brutality; it gives voice to painful events at the intersections of race/ethnicity, class, gender, language, sexuality, and residency status and honors marginalized peoples’ experiences, collective ancestral knowledge, and consciousness-raising (Delgado Bernal et al., 2012; Latina Feminist Group, 2001; Menchú, 1984/1997). Because of the capacity that Testimonio has to trouble power inequities, its practice within academia as pedagogy, epistemology, and methodology enables women of color particularly to usurp the hegemony of Western academic knowledge situated as truth (Cervantes-Soon, 2012) and brings consciousness to anti-oppressive work (Delgado Bernal et al. 2012). Testimonio as a pedagogical approach and research methodology in teacher education signifies not only a tool for change but change itself. Testimonio situates critical educators and students of color to lead the charge to design healing spaces within academia and fosters belonging for knowledge and wisdom gained within communities that experience historical and ongoing traumas and engage collective resistance/resilience and continue to build hope. Through Testimonio pedagogy, the teacher education classroom becomes a space wherein “the personal becomes political, and knowledge and theory are generated and materialized through experience…As the narrator tells [their] story, [they] break the silence, negotiate contradictions, and recreate new identities beyond the fragmentation, shame, and betrayal brought about by oppression, colonization, and patriarchy” (Cervantes-Soon 2012, p. 374). We engage in this study because, as Peercy and Sharkey (2020) note, “[little] attention has been paid to the ways in which the teacher educator’s social, personal, and professional practices and identities interact with and affect learning experiences in their classrooms and programs” (p. 111). Testimonio as pedagogy and methodology breaks open spaces wherein She, where They, the organic intellectual within each of us (Levins Morales, 2001), including teacher educators, may find the means to agitate and disrupt the un-wellness of our educational institutions and (re)incarnate more joyful, hopeful alternative (Pinnegar & Hamilton, 2009). Testimonio pedagogy and research methodology allow teacher educators to reflect on their own positionalities and the inequitable systems which may perpetuate cognitive imperialism. It enables students, especially students of color, to center ancestral knowing emanating from experience and the wholeness of their being. Ultimately, Testimonio transforms educational spaces into, “sites of organic healing, critical consciousness, and agency” (Cervantes-Soon 2012, p. 373).

Methodology

We utilize a Self-Study Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP) methodology encompassing narrative, autoethnography, self-study, life history, phenomenology, and action research to expose and challenge our most deeply held beliefs as educators as well as dominant Eurocentric approaches of teacher education to bring about antiracism, educational justice, and healing (Pinnegar & Hamilton 2009, p. 70). The narrative portion of this self-study comes through our use of the antiracist feminist narrative approach of Testimonio which was both the pedagogical and methodological foundation of our original student-centered inquiry project. This methodological pairing within S-STEP enables us as teacher educators to not only “uncover ways in which [we] participate in racism, paternalism, or sexism…” (Pinnegar & Hamilton 2009, p. 58); it highlights our strengths and knowledge sites as women, scholars, and predominantly female teacher educators of color who ourselves are the inheritors of these pedagogies of resistance, resilience, and transformation amid histories of oppression.

Data Collection

We utilize and expand upon "found poetry" (Edge & Olan, 2021) as data collection which “borrow[s] words from existing texts and then arrange those words to create an original poem” (p. 230). We began in the fall of 2022 by writing one poem formed by sampling, remixing, and blending excerpts of, 1) our own researcher journals during the fall of 2020, 2) transcribed research conversations over two years, 3) snippets of anonymized youth data, and stitched these excerpts together with 4) new threads of our reflective "today voice" speaking through self-study. Our "today voice" added context, filled gaps, and enriched the poem with contemporary insights. By weaving that which is "found" with that which is "freshly made," we established a hindsight vantage point and likewise bound our present self—She today, to We then who worked to make meaning of curriculum, pedagogy, and youth Testimonios. Our individual poems written as data collection during this present study conveys our experiences in the fall of 2020, our own social justice commitments and pedagogies, and growing understandings surrounding ourselves as educators.

Data Analysis

During one particular two-hour in-person focus group meeting, we each brought four printed copies of our newly written poems and handed them out to all members of the research team until each member had a packet of all four poems which were color-coded according to author/researcher. Silently and individually at first, we utilized highlighters to underscore lines in our poetry packet that were particularly salient across the four poems. We utilized scissors to cut out the highlighted excerpts from our four-poem packet. We then shared our findings and discussed the meaning our text selections had for us, for understanding our learning space, and what implications these had for teaching and teacher education. We reserved a space on the table for our paper strip excerpts and formed piles of excerpts that we decided were especially meaningful and likewise, those which were repeatedly selected. We discussed each pile, including data excerpts that were most thematically salient, and threaded these poetry strips into a larger tapestry poem (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2022). In the sacred space between us, we created one large tapestry poem which, 1) captured shared experience as students and teacher educators during fall 2020, 2) wrestled with our tensions in the field as women and educators, and 3) revealed the blending and bending of our knowing—our epistemology of practice as teacher educators (Martin & Russell, 2020).

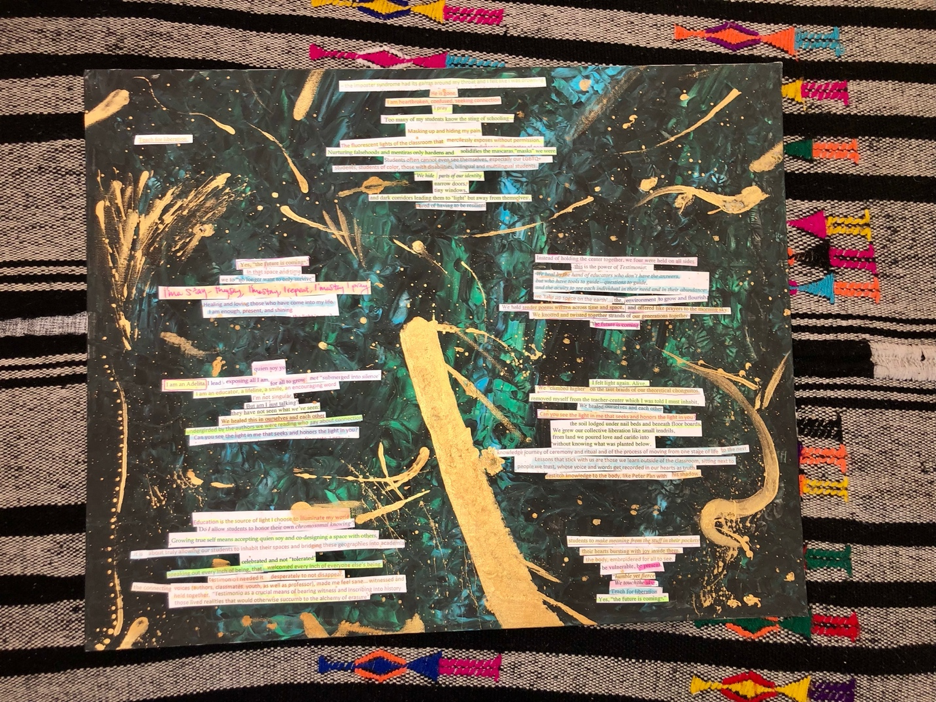

This process of collective poetic artmaking as data collection, analysis, and demonstration of Findings (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2022) became an act of polyvocality transcending the voice of one member. It underscored a larger unified though multitudinous knowing, brought a chorus of consciousness together, and centered creativity and play in analysis (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2022). This process gave way to a deep and multilayered knowing that, as female scholars, is often left at the 'doors of schooling' (Levins Morales, 2001). Together, we braided our historical and contemporary voices within our distinct poems and brought our writings together as an exhibition on one canvas which Helena later painted as an extension of the joyful criticality which was this work.

Trustworthiness

As Luttrell (2010) notes, seeking new kinds of knowledge requires advanced and multilayered methodologies and novel, expansive approaches to "validity" which include reliability, trustworthiness, and reciprocity at all stages. Our chronologically fluid tapestry poetry methodology borrows from Hamilton’s (2021) looking back to move forward approach in order to more deeply understand the “intricate, complex and evolving patterns and experiences within the ever-changing educational field of teacher education” (p. 209). We expand upon Hamilton’s (2021) looking back analytical approach to move and speak and write forward as well. Through poetic weaving of past and present voices, our selves of today communed with each other and our yesteryear selves as poets and critical friends, as comadres, female co-mother kindred spirits committed to antiracist, empowering, and womanist ways of knowing (Trinidad Galván, 2015).

Findings

As 13th century poet Rumi writes, "the wound is the place where light may enter." This self-study reveals the transformational power of pedagogically integrating our own intergenerational narratives of (im)migration, gendered oppression, racial/linguistic Othering, assimilation/cultural erasure, as well as the wisdom emanating from our spiritualities, cross-group working-class tenacity, matrilineal traditions of resistance/resilience, and mind/body/spirits as female educators teaching and living "in the colonies" (Pendleton Jiménez, 2006). This tapestry poem—woven from our newly-authored and thematically selected phrases—demonstrates how vulnerability and mind/body/spirit knowing became our most sacred offering to the teacher education classroom (see Appendix for transcription and color-coded analysis).

Figure 1

Tapestry Poem, Teaching for Liberation: The Future is Coming

While the first stanza utilizes, “garras [claws] around my throat…I am heartbroken,” “hiding my pain,” “mercilessly expose,” “narrow doors, tiny windows,” and “mentiras [lies]” to express the darkness, lovelessness, and restriction of White dominant schooling, the second and third sections offer healing and light in response. The reader will note themes of not only 1) pain but also 2) collectivity, reclamation, 3) land/soil/body connection, and 4) teaching as sacred ceremony of hope. While each is important, we explore these last two themes—3) land/soil/body connection, and 4) teaching as sacred ceremony of hope—in detail.

Theme 3: Land/Soil/Body Connection

In section two and increasingly in section three, themes of land/body connection and flourishing are visible within pedagogical language:

chromosomal knowing

Growing true self

bridging…geographies into academia

We ‘take up space on the earth’

grow and flourish.

strands of our generations—

soil lodged under nail beds…

we grew our collective liberation like small tendrils

Re-stitch knowledge to the body

… embroidered for all to see.

In these words, we tap into land rootedness and embodied, inherited knowing to open spaces of belonging for students’ emotional/psychological wisdom and the layers of history which live within our generations and our very cells (Delgado Bernal, 2006). Our collective poem reveals that growth and connection live at the center of our collective pedagogy and that our commitments to integrating land and body epistemologies are likewise at the heart of the next theme we detail teacher education as sacred practice.

Theme 4: Teaching as Sacred Ceremony of Hope

In section one, prayer, sacred ceremony, and hope peek through the cracks between pain and restriction with the words, “seeking connection” and “I pray”. By section two, evidence of this theme grows:

the future is coming

I’ma stay, I pray

Healing and loving

shining

we healed this

source of light…illuminate my world.

witnessed and held together

By section three, this same hope as sacred ritual nearly eclipses how we express the essence of our work:

we held tender poems…

…offered like prayers to the morning sky.

We “climbed higher”

healed ourselves.

journey of ceremony and ritual

recorded in our hearts as truth.

“humble yet fierce,

we touch the sky”

Yes, "the future is coming".

In these lines, teaching as ceremony reverberates and illuminates our shared ethic of teacher education practiced as love, healing, radical belonging, social justice, and flourishing. We honored ancestral knowing, distinctly embodied identities, ancestral and personal resistance, and our “humble yet fierce” hearts as antiracist educational practitioners.

Discussion

Centering pre-service educators’ knowing and curiosity within inquiry is, “challenging, emotionally taxing, and at times risky…[with] no easy answers” (Taylor & Diamond, 2020, p. 4). Through self-study, we came to understand the role of our own vulnerability and educational striving within the Testimonio Curriculum Lab and the potential our work has for fortifying teacher education as transformation. This self-study renewed and enlivened our professional purpose (LaBoskey & Richert, 2015), reminding us to approach through intergenerational experience and mind/body/spirit essence.

By the light of our students’ Testimonios and our own, we hallowed the ground. Together, we explored the ills of assimilationist epistemologies in dominant schooling and gave space to the multitude of organic remedios we each bring. By enacting Testimonios as antiracist, womanist critical consciousness in inquiry, we cultivated a landscape wherein future educators are supported to foster multiple literacies of resilience, collectivity, belonging, and self-love as well as curricular creativity to design social justice curriculum around youth multiliteracies and community wealth.

Vulnerability and joy—including the sheer messiness bursting through our multicolored creation—were/are essential to educational justice (LaBoskey & Richert, 2015). These findings convey Testimonios’ resistant, healing potency to expose and challenge racism, xenophobia, queerphobia, sexism, ableism, and erasure of the especially female body and to live out the full power of voice and cultural knowledge in academia. By exploring familial narratives, vulnerability, and hopeful dreaming in teacher education, we alongside our students could “bear witness to each other” and ultimately “touch the sky”.

References

Anzaldúa, G. E. (2015). Light in the dark/Luz en lo oscuro: Rewriting identity, spirituality, reality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Battiste, M., & Henderson, J. Y. (2000). Protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: A global challenge. Purich.

Beach, R., Campano, G., Edmiston, B. & Borgmann, M. (2010). Literacy Tools in the Classroom: Teaching Through Critical Inquiry, Grades 5-12. NY: Teachers College Press.

Blum Martínez, R., & López, M. J. (Eds.) (2020). The shoulders we stand on: The history of bilingual education in New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

Cervantes-Soon, C. G. (2012). Testimonios of life and learning in the Borderlands: Subaltern Juárez girls speak. Equity & Excellence, 45(3), 373-391.

Delgado Bernal, D. (2006). Learning and living pedagogies of the home: The Mestiza consciousness of Chicana students. In D. Delgado Bernal, C. Elenes, F. Godinez, & S. Villenas (Eds.), Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminista perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology (pp. 113–132). State University of New York Press.

Delgado Bernal, D., Burciaga, R., & Flores Carmona, J. (2012). Chicana/Latina testimonios: Mapping the methodological, pedagogical, and political. Equity & Excellence, 45(3), 363-372.

Díaz Soto, L., Cervantes-Soon, C., Villareal, E., & Campos, E. (2009). A Xicana sacred space: A communal circle of compromiso for educational researchers. Harvard Educational Review, 79(4), 755-775.

Edge. C. U. & Olan, E. L. (2021). Learning to breathe again: Found poems and critical friendship as methodological tools in self-study of teaching practices. Studying Teacher Education, 17(2), 228-252.

Gonzales-Berry, E., & Maciel, D. (2003). The contested homeland: A Chicano history of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

Hamilton, M. (2021). An ethic of care and shifting Self-Study Research - Weaving the past, present, and future. In C. Edge, A Cameron-Standerford, & B. Bergh (Eds.), Textiles & Tapestries: Self-Study for Envisioning New Ways of Knowing (pp. 209 - 219). EdTechBooks.org.

Kliebard, H. M. (2004). The struggle for the American curriculum: 1893-1958. Routledge Falmer.

LaBoskey, V. K., & Richert, A. E. (2015). Self-Study as a means for urban teachers to transform academics. Studying Teacher Education, 11(2), 164–179.

Latina Feminist Group (Ed.) (2001). Telling to live: Latina feminist testimonios. Duke University Press.

Levins Morales, A. (2001). Certified organic knowledge. In Latina Feminist Group (Eds.), Telling to live: Latina Feminist Testimonios (pp. 27-32). Duke University Press.

Lomawaima, K., & McCarty, T. (2006). “To remain an Indian”: Lessons in democracy from a century of Native American education. Teachers College Press.

Luttrell, W. (Ed.) (2010). Qualitative educational research: Reading in reflexive methodology and transformative practice. Routledge.

Martin, A. K. & Russell, T. (2020). Advancing an epistemology of practice for research in self-study of teacher education practice. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. M. Bullock, A. R. Crowe, M. Taylor, H. Guðjónsdóttir, L. Thomas (Ed.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 1045-1073). Springer.

Martinez, G. (2010). Native pride: The politics of curriculum and instruction in an urban public school. Hampton Press.

Menchú, R. (1997). Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú y así me nació la conciencia. In, I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian woman in Guatemala. (A. Wright, Trans.). Verso. (Original work published 1984).

Mexico Law and Poverty Center. (n.d.). http://nmpovertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/D-101-CV-2014-00793-Final-Judgment-and-Order-NCJ-1.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2020). Characteristics of public and private elementary and secondary school teachers in the United States: Results from the 2017-2018 National Teacher and Principal Survey. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020142.pdf

New Mexico Voices for Children. (2020). New Mexico kids count data book: Building on resilience. New Mexico Voices for Children. https://www.nmvoices.org/archives/15123

Peercy, M. M., & Sharkey, J. (2020). Missing a S-STEP? How Self-Study of Teacher Education Practice can support the language teacher education knowledge base. Language Teaching Research, 24(1), 105–115.

Pendleton Jiménez, K. (2006). “Start with the land”: Groundwork for Chicana pedagogy. In D. Delgado Bernal, C. Elenes, F. Godinez, & S. Villenas (Eds.), Chicana/Latina education in everyday life: Feminista perspectives on pedagogy and epistemology (pp. 219–229). State University of New York Press.

Pinnegar, S., & Hamilton, M. L. (2009). Self-study of practice as a genre of qualitative research. Springer.

Pithouse-Morgan, K. & Samaras, A. P. (2022). “Risky, rich co-creativity”: Weaving a tapestry of polyvocal collective creativity in collaborative self-study. In B. M Butler & S. M Bullock (Eds.), Self-study of teaching and teacher education practices, vol 24, pp. 203-217. Springer.

Rendón, L. I. (2009). Sentipensante (sensing/thinking) pedagogy: Educating for wholeness, social justice and liberation. Stylus Publishing.

Sosa-Provencio, M. A. & Sánchez, R. (2020). Serna v. Portales: Changing the music and asserting language rights for New Mexico’s children. In R. Blum-Martínez & M. J. Habermann López (Eds.), The shoulders we stand on: The history of bilingual education in New Mexico (138-161). University of New Mexico Press.

Suina, J. (1985). “And then I went to school”: Memories of a Pueblo childhood. New Mexico Journal of Reading, (5)2.

Taylor, M. & Diamond, M. (2020). The role of self-study in teaching and teacher education for social justice. In J. Kitchen et al. (Eds.) 2nd international handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education, pp. 1-35. Springer. Retrieved from: https://www.montclair.edu/profilepages/media/437/user/2020taylordiamondselfstudy.pdf

Trinidad Galván, R. (2015). Women who stay behind: Pedagogies of survival in rural transmigrant Mexico. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

U. S. Census. (2019). QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NM

Valenzuela, A. (Ed.) (2016). Growing critically conscious teachers: A social justice curriculum for educators of Latina/o youth. Teachers College Press.

Yazzie/Martinez v. State of New Mexico (2018). First judicial state court judgment. New Mexico Law and Poverty Center. http://nmpovertylaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/D-101-CV-2014-00793-Final-Judgment-and-Order-NCJ-1.pdf

Appendix A

Tapestry Poem: Teach for Liberation: The Future is Coming

[Section One: Located at top middle]

…the imposter syndrome has its garras [claws] around my throat

He is gone,

I am heartbroken, confused, seeking connection[3].

I pray.

Too many of my students know the sting of schooling—

masking up and hiding my pain.

The fluorescent lights of the classroom that mercilessly expose without permission.

Nurturing falsehoods and mentiras [lies]

only hardens and solidifies the mascaras, “masks” we wear.

Students often cannot even see themselves,

especially our LGBTQ+ students, students of color, those with disabilities,

bilingual and multilingual students…

We hide parts of our identity[4]

narrow doors,

tiny windows,

and dark corridors leading them to ‘light’

but away from themselves-

tired of having to be resilient.

[Section Two: Located on left-hand-side]

Yes, “the future is coming[5]”

In that space and time

We, too, “no longer want to only survive”

I’ma stay—they say—I’ma stay, I repeat, I’ma stay, I pray

Healing and loving those who have come into my life.

I am enough, present, and shining.quien soy yo [who am I]

I am an Adelita[6]. I lead, exposing all I am for all to grow,

not “submerged into silence”

I am an educator, a lifeline, a smile, an encouraging word

I’m not singular.

But am I just talking?

They have not seen what we’ve seen:

We healed this in ourselves and each other.

undergirded by the authors we were reading

who say that about connection.

Can you see the light in me that seeks and honors the light in you?Education is the source of light I choose to illuminate my world.

Do I allow students to honor their own chromosomal knowing?

Growing true self means accepting quien soy [who I am]

and co-designing a space with others,

…it is about truly allowing our students to inhabit their spaces

and bridging these geographies into academia

celebrated and not “tolerated”

speaking out every inch of being,

that welcomed every inch of everyone else’s being

testimonio I needed it desperately to not disappear.

The connecting voices (authors, classmates, youth, as well as professor),

made me feel sane…

witnessed and held together.

“Testimonio as a crucial means of bearing witness and inscribing into history

those lived realities that would otherwise succumb to the alchemy of erasure”

[Section Three: Located on right-hand-side]

Instead of holding the center together, we four were held on all sides.

this is the power of Testimonio.We heal by the hand of educators who don’t have the answers,

but who have the tools to guide—questions to guide,

and the acuity to see each individual in their need and in their abundance.

We ‘take up space on the earth’…the environment to grow and flourish.

We held tender poems written across time and space,

and offered like prayers to the morning sky.

We knotted and twisted together strands of our generations—“the future is coming”

I felt light again. Alive.

We “climbed higher” on the taut braids of our theoretical chonguitos

removed myself from the teacher-center which I was told I must inhabit,

We healed ourselves and each other.

Can you see the light in me that seeks and honors the light in you?

the soil lodged under nail beds and beneath floor boards.

We grew our collective liberation like small tendrils,

from land we poured love and cariño [warm, responsive caring] into

without knowing what was planted below.

knowledge journey of ceremony and ritual and the process of moving

from one stage of life to the next.

Lessons that stick with us are those we learn outside the classroom,

sitting next to people we trust,

whose voice and words get recorded in our hearts as truth.

Re-stitch knowledge to the body, like Peter Pan with his shadow.students…make meaning from the stuff in their pockets

their hearts bursting with joy inside them.

the body, embroidered for all to see.

be vulnerable, be present.“humble yet fierce,

we touch the sky”Teach for liberation

Yes, “the future is coming”

Thematic coding key:

Pain, restriction

Collectivity

Resistance, reclamation.

Sacred, affirming, healing, hopeful

Organic, land/soil, body connected

[1] We use the term 'Indigenous' to describe New Mexico’s Native American communities, individuals, and languages—this nomenclature was selected for its common usage by Indigenous scholars in this place. We use 'Native American' only when sources list it as demographic designation.

[2] To name New Mexico’s Spanish-speaking People(s) of blended Indigenous, African, and Spanish ancestry formed within Spain’s 16th century conquest of Mexico and present-day Southwest, we utilize the geographically and culturally specific term 'Nuevomexicana/o'. We use the broader term 'Mexicana/o' (encompassing Mexican/Mexican American families arriving in the 20th century and long standing Nuevomexicana/o communities) to name the entirety of New Mexico’s Spanish-speaking population. The term 'Hispanic' is used only when citing demographic designations in governmental reports.

[3] Jackie’s reflection written in response to a former high school student of hers who committed suicide.

[4] High school youth data

[5] High school youth data

[6] Female soldiers during the Mexican Revolution—symbolic and literal figures of female strength, community protection, solidarity.