“We Are Going to Need a Bigger Bottle”

Surfacing and Leveraging a Decade of Relational Knowledges

Context and Objectives

[People said]..., ‘oh, have your fun...you're gonna fall apart.’ And ... if we're only working within the structures that we’re given in academia, we're going to fall apart. But if we engage with the trauma, and we create alternatives that continue to be fulfilling, so that we can become otherwise, then we subvert the system, and [create] something new... doing academia differently and affirmatively. (Et Alia Dialogue, 7/18/21)

The four of us are a self-study collective who have been working together for an extended period of time. As summer 2021 dawned, eighteen months into the COVID-19 pandemic, we found ourselves feeling fractured as a group and uncertain about our future together. In response, we planned a three-day retreat in a remote coastal area and engaged in a series of discussions to navigate our healing process and decide what we wanted the future of our group and collective self-study work to look like--or indeed, whether we wanted a future together at all.

In this paper, we inquire into a process of self-study community redevelopment and healing in the aftermath of a global pandemic, examining the retreat as a critical moment. Our aim is to identify what facilitated this redevelopment-healing process. Utilizing critical complexity perspectives, we employed the Listening Guide (Gilligan, 1982) to analyze the personal-professional entanglements that emerged during the writing retreat, focusing on affects/power flows and materialities. From this analysis, we constructed several types of relational knowledges that we had developed over time, through different phases of career/life, that served as facilitating tools. We use these analyses to discuss how the process of self-study enabled the growth of our relational practices to support ongoing healing and sustain a commitment to engaging with/in academia affirmatively.

Conceptual Framework

To frame our study, we draw on critical complex and feminist perspectives. By “critical complex” perspectives, we mean a continuum of trans-disciplinary theoretical orientations that resist rational humanism and anthropocentrism (Braidotti & Hjavalova, 2018), which underscore dominant, white, masculinist ways of thinking (Braidotti, 2013). Instead, critical complex perspectives emphasize a relational, multiplistic, difference-rich, explicitly political, always-in-process onto-epistemology (Strom & Viesca, 2021) that attends not only to human elements but also the non-human (Bennett, 2010)--both in terms of material (e.g., physical objects, places) and incorporeal (e.g., discourses, affects, power flows) (Barad, 2007; Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). In such a perspective, individual humans are not the solely agentic actors and narrators of our reality. Social activity, rather, is produced collectively by assemblages–that is, temporary constellations or multiplicities of human-nonhuman elements suffused with affect (e.g., relational forces that increase or decrease one’s capacity to act per Massumi (1987). They are also intra-active (Barad, 2007): in other words, the elements present are co-constitutive, or collectively co-create each other.

We have drawn on these ideas to theorize that our work is enabled by more-than-human critical friendship, or a relational becoming that spans the material, corporeal, and affective, “an assemblage of our bodies, histories, shared experiences, common knowledges and language, intimate knowledge of each other, and collective identity” (Mills et al., 2020, p. 484). This relationship assemblage is itself an agentic actor in our knowledge-practice transformations over time, both individually and as a collective, as we sustain and affirm ourselves in neoliberal systems.

Methods

We draw on LaBoskey’s (2004) criteria for self-study research which helps us to better understand how we, our relationships, our practices, and our world are co-constituted, often through our dialogue and embodied experiences, in composition with agentic other-than-human elements (Strom et al., 2018). We are engaged in a “more than critical friendship” (Mills et al., 2020) to construct knowledge that moves beyond our collective to provide implications for the larger field (Loughran, 2005). In light of our question, “What enabled the (ongoing) redevelopment-healing process of our self-study collective and how might this inform our self-study practice?” We employed Gilligan’s (1982) Listening Guide, a feminist, relational, qualitative, voice-centered method of inquiry (Gilligan, 1982) as an analytic tool to examine audio recordings and transcripts from our retreat and six subsequent Zoom meetings.

The Listening Guide attuned us to our voices, both as individual self-study researchers and as a collective assemblage. The Listening Guide method requires the researcher to listen for three distinct types of information, starting with the “plot:” attending to who is speaking and to whom, telling what stories, and in what societal and cultural frameworks. Second, we listened for “I”/ first-person voice, or how participants speak about themselves. We highlighted what we said about ourselves in relation to others in the transcript, and used this highlighted text to write “I poems,” separating out each I phrase in order of appearance. These poems pick up distinct cadences and rhythms and “draw out the internal conversations so that they are audible and the nuances can readily be seen’’ per Raider-Roth as quoted in Woodcock (2016, p. 4). Next, we listened to the contrapuntal, which refers to “listening for different voices and their interplay, or harmonies or dissonances within the psyche, tensions with parts of itself” (Gilligan & Eddy, 2017, p. 79). From this listening, we noted that when we moved from individual stories to multi-voiced dialogue, we revealed different layers of our experiences and facets of the stories we told (Brown & Gilligan, 1992). We also noticed gaps, conflicting understandings, or responses that we revisited for clarification. The final stage of the Listening Guide helped to explore themes and how they related to one another. Building on emergent themes, we engaged in focused coding using the following analytic questions:

- What are the material/discursive/human elements in this assemblage?

- What might the intra-action among those elements be doing/producing in terms of affect, powerflow, and materialities?

- What tools/affordances were available or produced to support our collective process of coming into a renewed relationship?

The inquiry and analysis procedures of The Listening Guide (Gilligan, 1982) were challenging but effective, and not impervious to the inherent limitations. During this study, we explored the concept of voice and what it can do: we also found clues that later revealed hidden, withheld, or difficult-to-express feelings by returning to these pauses during further analysis. Breaks in dialog proved to be areas to mine later; they revealed tensions and complex emotions that required looking below the surface of what was initially said, and these even concealed or revealed withheld feelings. The opportunities and the challenges presented in using a voice-based method were myriad: simply listening to our meetings together, and focusing on our voices was often not enough to be able to really hear what each of us was saying. Our authentic yet sometimes incomplete reflections about our healing process required further probing and analysis between the second and third listenings.

Findings

Material-Affective-Discursive Elements of Our Assemblage(s)

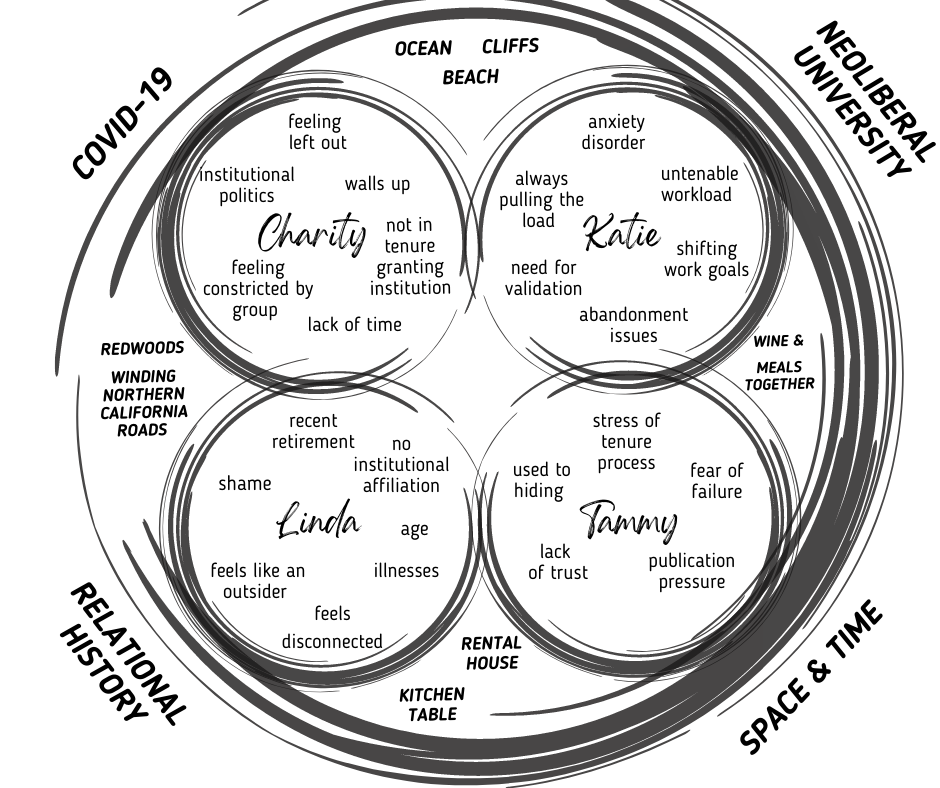

Within the distinct time and space of our Irish Beach retreat, we collaboratively constructed an understanding of the macro-level overarching forces that were having material and affective impacts on us individually and collectively (see Figure 1). These forces, including the coronavirus pandemic, neoliberalism, space/time, and our relational history, framed and infiltrated our conversations, elicited emotional responses and reverberated in our bodies. The local material surroundings we encountered at Irish Beach were also agentic for expressing our authentic experiences, needs, power flows, and material circumstances. There, we were awed by the beauty of the place, challenged by its wildness, nourished with plentiful food and wine, and cradled in the house perched on a cliff. Sharing, listening to, and connecting with each other as multiplicities we carried with us to the retreat produced an open-heartedness–a physical and emotional effect of mutual empathy and vulnerability. In concert, the three layers of intra-acting assemblages–macro-level, local, and personal, and each composed of material, discursive, and human elements–comprised our collective “Irish Beach” assemblage (Figure 1). Understanding that the whole of our assemblage did not pre-exist the connections that created it, we were inspired to examine these entanglements for new ways of being in a relationship together upon our return home.

Figure 1

Assemblages

During our time at Irish Beach, we identified, deconstructed, and repurposed the conditions that contributed to the unraveling of the ties that had previously bonded us. The COVID-19 pandemic, pressures and barriers of our neoliberal institutions, space/time, our own life changes, and our sometimes damaging patterns of interactions operated as forces of relational disconnection. Attending to how these affected our capacity to maintain and grow our relationship, we confronted and challenged the ways these forces acted to assert their dominance. For example, we recognized the material affects of academia, including dominant systems of thought, employment practices, and research and publication standards, that determine how and to whom power flows. When Tammy took a bedroom far removed from the others and spent time separated from the group, it was noticed, discussed, and taken up as a group. Tammy shared a complex work situation that implicated the tenure process, including the forced isolation of academia, something that had slowly, but steadily, been overwhelming her for the past few years. At that particular moment, Tammy was stressed about a specific proposal and deadline. Listening to her and reconnecting across common experiences of our subjectivity as being in relation with academia activated empathetic responses to Tammy’s situation and thereby regenerated our capacity for being in-relation-with each other and worked to transform our relationship.

We also took accountability for interrogating the affect of our relational history on our work. While it was pleasant to conjure our shared history through metaphors and short-hand references to experiences we shared, such as “Le Reminet”, “nasty women”, and “at the table”, and to use them as touchstones for understanding what we are becoming, our analysis also showed that we raised our awareness of more damaging elements of our shared history such as how power flowed through our group. We saw this play out in an exchange during the retreat when in response to a comment from Charity about dominance in the group, Katie drew attention to the pressure she felt to complete work explaining, “... we've fallen into patterns about who takes the lead on things. And so... I was kind of compelled to take the lead or for whatever reason felt like I had to.” The comment led to a discussion on how and whether our individual and collective needs were being met, revisiting these in light of changes in our individual personal-professional circumstances, and responsibilities. We concluded that to become otherwise, we had to be more intentional in how we organize our time and work together. Articulating these circumstances and examining them in connection to the way they affected our relationship as a self-study collective was an affordance in our redevelopment process.

Irish Beach was an occasion for recognizing the materiality of our bodies–ways we are different when we move away from our shared workspace, the table. The home where we stayed abutted the Anderson Valley wine region of northern California–a good thing, because to get through the difficult conversations we planned, one of us joked, “We’re gonna need a bigger bottle.” The local wine and food were agentic for deepening our relationship as we relaxed and exposed intimate details of our lives beyond our collective relationship. Walks on the beach, over piles of driftwood and up the cliff where the Irish Beach house perched, highlighted our deep relationality to nonhuman entities and the limitations of believing we are autonomous and capable on our own. Car rides on winding roads in which we were physically separated by the partition between the front and back seats alerted us to divisions in our relationship and prompted two members to share their hurts around patterns of interactions. Sharing their very different perceptions of those interactions, they constructed the understanding, “we define caring for others in very different ways.”

Exploring our individual and collective subjectivities during our time at Irish Beach, we learned that as a group we are composed of and intra-active with overarching macro-level forces, our personal and shared histories, our human bodies, and the discursive and material contexts that connect us. We learned that our relationship is dynamic and affectual with active agency to sustain and transform us when we engage in the relational affects of mutual vulnerability and empathy and learn from and with each other--“to become in relation to”.

Relational Knowledges and Other Facilitating Agents

Each of us arrived at Irish Beach with a story of how the pandemic was affecting us personally and professionally. With time spent in person reminiscing over shared memories, over the span of several days we found the courage to share our difficult feelings about one another together in a safe honest shared space. This dialogue turned into one of many conversations exploring our relational patterns. Ultimately, they yielded a set of relational knowledges, which we identify as understandings that are created from or emerge from relationships over time and across locations. They are both individual and collective and are constructed from our histories, our experiences together, including the experience of data analysis. These relational knowledges became tools for us to identify powerful aspects of our work together, as well as forge new ways of being together that met each of us where we were, leaning into the ebb and flow of our relational assemblage.

We Develop and Renew Seed Knowledge

The first type of relational knowledge, which we see as a sort of seed knowledge that is integrated through everything, is our complex understandings of each other individually and as a collective. In our shared decade of history, we have loved and cared about each other, supported each other through hard times and celebrated life milestones. We self-studied, traveled, cried, and laughed together–and in the process, we learned every aspect of each other’s lives: our upbringings, our strengths and joys, our insecurities, and our fears. We also have learned how we, as a collective, have interacted over time, which creates opportunities for us to enact agency in particular ways.

To represent our seed knowledge as the product of the intra-action of personal and collective self-understanding, we provide below excerpts from an Irish Beach conversation. We had returned from a walk on the beach which included a strenuous scramble over piles of driftwood. In these excerpts, Linds’s first person voice is identified by underlining and her second person voice is bolded.

Being at this place in my life. It's like I feel like a stranger in a strange country…I just so thank you for pulling me back in. There's another thing that's gone on for me. And I think I don't know if this is hard for you to understand, because I'm not you. I'm thinking of myself. As a younger woman, it would have been hard for me to understand.

Here, we see Linda’s first person voice intra-acting with knowledge of self-in-relationship to our Irish Beach assemblage. While she grappled with her vulnerability as an older person, she began to clarify her emotive and embodied experiences and knowledge of her connections to and within the assemblage. After nearly two years of separation from the group, the conditions that created Linda’s subjectivities required renegotiation. Thus, she drew upon our collective seed knowledge to rebuild her knowledge-of-self in relation with renewed enthusiasm for what the group was becoming.

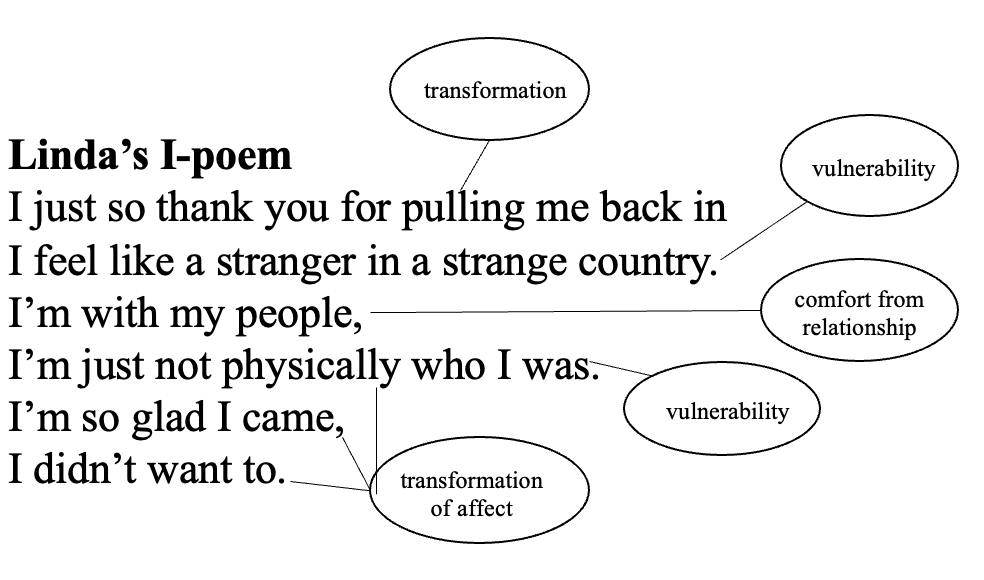

Linda continued to distill her knowledge of self-in-relation by recapturing the knowledge-producing experience of Irish Beach in the following I-poem (Figure 2.), composed and analyzed during a Zoom meeting following the retreat.

Figure 2

I-poem

The I-poem reflects a transformation in Linda’s seed knowledge about the affects of our relationship, including vulnerability, connection, comfort, and openness to transformation, that facilitate our longevity as a dynamic and productive collective.

We Leverage Our Bonds of Affection

Woven through each of the individual stories we shared were specific requests for support that invoked the power of our relationship for overcoming professional challenges. For instance, when describing feeling “stuck”, a member of the group connected to another’s journal entry and commented, “...we’re like supporting each other on doing a better job at being us on the things that we're working on...it's such personal learning, even though it's connected to our professional selves.” We understood that by leveraging our bonds, including our knowledge of each other and our individual work, we are able to amplify or augment our resilience for working within neoliberal systems that foster individualism, competition, and productivity.

Returning to Linda’s example above, we noted that her initial comment about feeling “like a stranger in a strange country,” was entangled with her experience of being retired from her position at an education foundation. Arriving at Irish Beach, she was uncertain about what she would have to contribute and whether she would be able to continue as a member of our self-study collective. However, Katie reacted to Linda’s estrangement, “...working with you, as part of our relational collective, right, that makes us collectively better individually and fulfilled. And when I say better…I mean, like enhanced.” Tammy added, “...we are otherwise we would not be the same without you”. Because Irish Beach enabled us to reassemble in ways that opened new intersections and connections, Linda could envision new ways of contributing to our work and how she and the collective would adapt together.

I was able to recognize my own power and privilege because I am not hindered by a full-time job or stressed to be productive. This freedom opened-up possibilities for how I could position myself in the group. I was also able to shed my sense of being a victim of the system which gave me the confidence to examine my part in the breakdown of our relationships.

Linda assumed an affirmative stance in taking up her power and privilege in recognition of the freedom available to her in retirement to pursue the role of mentor, interrupting our habits of thinking about “worth” as being limited to our paid work.

We recognize that the personal-professional resilience we are developing together has active agency and matters beyond our group to transform relations with and in academic institutions. By intentionally attending to our entangled professional-personal relational assemblage we are able to “do academia differently”--not only to ensure our own thriving in such systems but also as broader interventions to disrupt the conditions of academia. For example, in one of our meetings Tammy shared a conversation she had with a doctoral advisee: “… you cannot do this work by yourself…you have to have a group of people that you trust and have a relationship with.” Our knowledge that developing affirmative bonds of affection can generate the power to act differently in harmful conditions is applicable to our everyday practices. As such, we understand that working in solidarity with colleagues, challenging power dynamics and institutional structures that marginalize and alienate us has potential for transformation beyond us.

We Disrupt Patterns of Interaction

During our time at Irish Beach, we surfaced and discussed ways power flowed in our collective to influence the roles we played when we worked together and our more general patterns of interactions. We came to understand that our lack of attention to and consideration for changes in our individual circumstances generated unvoiced hurts that had accumulated. During one of our follow-up meetings Katie commented that the pandemic had stopped time in some way, ”...but we all did change. We are all in the process of renegotiating.”

We were challenged to reconsider assumptions about our collective as a cohesive unit, characterized by stability over time. Linda revealed, “Although we had agreements about working outside the group, the way we have done it makes me feel left out”. On the unpredictable flow of power during one conversation, Tammy observed, “[In CA as we talked] I could feel it shifting and changing lots of assets flowing through our group, the mood the temperature the vibe whatever…I could sense it so many times and I couldn't say anything which I found really interesting.” Aware of the tension, the energy produced at the intersections of power in the group, Tammy tested what it would be like to detach from us and decided to engage intellectually but not emotionally in our conversation, reverting to deep-rooted ways of shielding herself from the conflict that coincides with connection.

As the retreat progressed, we came to an understanding that we needed to think differently about our challenges and intentionally disrupted patterns of participation that had become status quo so that our power relations could become more flexible. We agreed that roles for the production of this paper would be shifted to allow Katie a respite from the pressure of “always having to be productive” and to open space for others to take the lead. Our knowledge of the possibilities of this change was partial at the time, but later, as we analyzed data in ways we had not previously considered, we learned that we were capable of rebuilding our relationship as an assemblage of ever shifting, always expanding opportunities for renewal.

Conclusion

The material-discursive assemblage of Irish Beach and the relational knowledges we developed in that space and time mattered in terms of enabling us, as a self-study collective, to move forward and heal. As one of us wrote, “I thought this was going to be the death of us, but it is actually a rebirth.” At the heart of this process of redevelopment and healing was our shared subjectivity which we claimed by writing this paper. We understand self-study as a deeply personal, vulnerable, and creative project that affirms the importance of belonging to a community of educators and rests on the endurance of relationships with members who will act as more-than-critical friends. For us, critical friendship extends beyond the research project to encompass opportunities for expansion of the self-in-relation with others. As such, self-study is a tool for liberating and transforming.

Extending our understandings into larger academic settings as a way of transforming gatekeeping and policing relations is part of our enactment of what Braidotti (2019) refers to as affirmative ethics: engaging with pain and trauma to generate shared knowledge, and then using that knowledge to rework negative affects that produce isolation, exclusion, anxiety, and burnout. Through this reframing, self-study has the potential to create new structures that enable support, collaboration, and proliferation (for another example of this reworking of negative academic affect, see Authors, forthcoming, on affirmative peer-reviewing practices).

We also bring our relational knowledges into our own teaching and mentorship practices by purposefully creating educational communities that value diverse ways of knowing, validate multiple experiences, and recognize vulnerability and relational resilience as essential to the learning process. Katie, for example, has added a community-building component to every class session: students collaboratively develop a set of collective agreements for learning together at the beginning of the course. Further, we encourage pre-service teachers, practitioners, and school leaders to turn their gaze outward, to enhance their understanding of their own practice by examining it with others, and to build relationships grounded in mutual vulnerability and support.

Finally, we see implications for relational knowledges in ethical qualitative research practice. In particular, from understanding the ways that our relational knowledge mattered in our analysis, we began to recognize that this process was a practice of relational reflexivity. In other words, our relationship (and its history and related knowledges) was part of the assemblage we brought to our analysis, and as such, became a mediating factor producing our reading of our data. However, typically in qualitative research projects with multiple researchers, reflexivity is something that is articulated on an individual level: for instance, each researcher might state her own positionality and offer how that might shape the knowledge production. Seldom do we address our relational positionality and the ways that might turn us toward and away from particular readings. We suggest that the idea of relational reflexivity is a topic worthy of further exploration.

References

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway. Duke University Press. DOI: 10.1215/9780822388128

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press. DOI: 10.1215/9780822391623

Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Polity Press. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2013.12.1.1

Braidotti, R. (2019). Posthuman knowledge. Polity Press. DOI: 10.3917/soc.150.0151

Braidotti, R., & Hlavajova, M. (Eds.) (2018). Posthuman glossary. Bloomsbury. DOI: 10.5040/9781350030275.0006

Brown, L. M., & Gilligan, C. (1992). Meeting at the crossroads: Women's psychology and girls' development. Harvard University Press. DOI: 10.4159/harvard.9780674731837

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). Capitalism and schizophrenia: A thousand plateaus. University of Minnesota Press.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women's development. Harvard University Press. DOI: 0.4159/9780674037618

Gilligan, C. & Eddy, J. (2017). Listening as a path to psychological discovery: An introduction to the Listening Guide. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6, 76–81. DOI: 10.1007/s40037-017-0335-3.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Kluwer. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3_21

Loughran, J. (2005). Researching teaching about teaching: Self-study of teacher education practices. Studying Teacher Education, 1(1), 5-16. doi: 10.1080/17425960500039777.

Massumi, B. (1992). A user's guide to capitalism and schizophrenia: Deviations from Deleuze and Guattari. The MIT Press.

Mills, T., Strom, K., Abrams, L. & Dacey, C. (2020). More-than critical friendship: A posthuman analysis of subjectivity and practices in neoliberal work spaces. In C. Edge, A. Cameron-Standerford, & B. Bergh (Eds.), Textiles and Tapestries. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/textiles_tapestries_self_study/chapter_14

Strom, K., Mills, T., Dacey, C., & Abrams, L. (2018). Thinking with posthuman perspectives in self-study research. Studying Teacher Education, 14(2), 141-155. DOI: 10.1080/17425964.2018.1462155

Strom, K. J., & Viesca, K. M. (2021). Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. Professional Development in Education, 47(2-3), 209-224. DOI: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1827449

Woodcock, C. (2016). The listening guide: A how-to approach on ways to promote educational democracy. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1). DOI: 10.1177/1609406916677594