Looking Into the Rear-View Mirror While Moving Forward

Drawing on Past Collaborative Experiences to Inform Present Practice

Context of the Study

As a longstanding cross-school/institution collaborative knowledge community (Craig, 2007) of U.S. teachers/teacher educators/researchers, we (researchers from the Portfolio Group) noted how the optimal experiences (Dewey, 1934) we have shared via Portfolio Group interactions have shaped our individual practice, fueling other collaborations (Craig et al., 2020a). Optimal experience is based on the concept of flow, “a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else [matters as much]; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it...for the sheer joy of doing it” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990, p. 4). For us, professional growth/development and generative space are deeply connected to the satisfaction found in collaborative group work. Our ongoing professional dialogue on current practice consistently reverberates with aspects that were enhanced through our group collaboration, providing a look in the rearview mirror if you will. The optimal experience shared via the Portfolio Group has not only shaped our work with colleagues but also prompted the formation of other collaborative groups.

Situated in a diverse metropolitan area of the southwestern United States, our group came together in 1998 around school portfolios (Lyons, 1998a, 1998b, 2010) as a way to evidence our school reform efforts. Guided and mentored by our schools’ Formative Evaluation Researcher, Cheryl Craig, we explored literature on how to evidence our work (Clandinin & Connelly, 1994; Eisner, 1997), shared our teacher/school stories, provided feedback, and developed relationships characterized by reciprocity and support. Alongside our group’s collaborative learning and interactions, we have participated together in numerous professional development opportunities. Looking back, these were often optimal experiences (Dewey, 1934) that informed, reformed, or transformed (Tidwell et al., 2012; see also Curtis et al., 2013) our individual and group/collaborative practice.

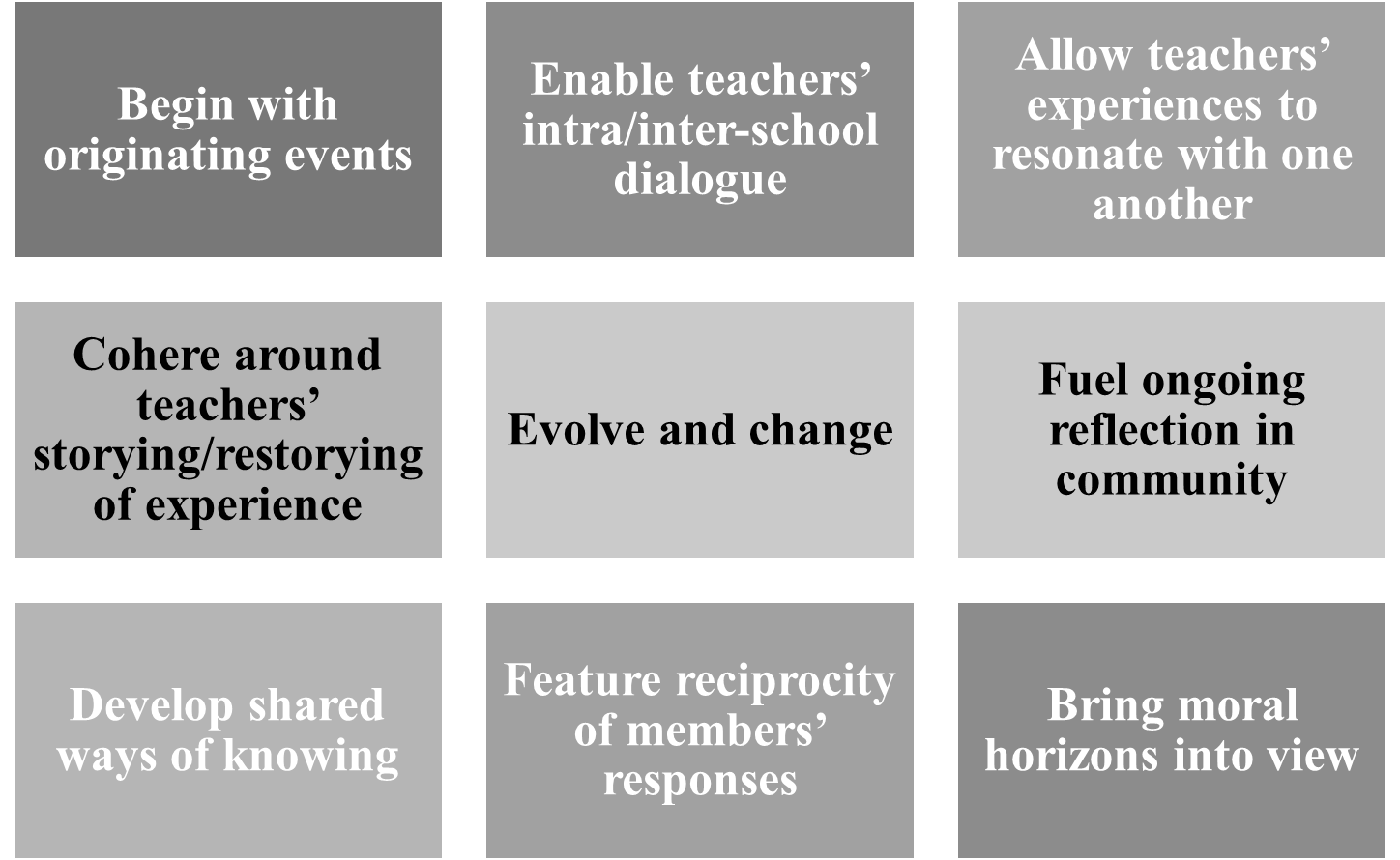

Working together over time, we came to see ourselves as a knowledge community (Craig, 2007) (see Figure 1) and our interactions as “safe, storytelling places where educators narrate the rawness of their experiences, negotiate meaning, and authorize their own and others‟ (Olson & Craig, 2001, p. 670) interpretations of experiences/situations. For example, the Portfolio Group began with an originating event, the group enables teachers’ cross-school dialogue, and the group has organically evolved/changed. Additionally, we cohere around our storying/restorying/reframing of experience (Craig, 2007) and provide time for experiences to resonate with one another alongside the reciprocity of member feedback. These commonplaces of experience promote ongoing reflection and community, yet also bring into view the moral horizons of the education landscape. These characteristics differentiate knowledge communities from other communities of learning/practice. For example, the primary aim of professional learning communities (Dufour & Eaker, 1998), Critical Friends Groups© (CFGs), and others is instructional improvement and school reform for accountability purposes at one school/institution (Curry, 2008). Unlike knowledge communities that “take shape around commonplaces of experience” (Craig & Olson, 2002, p. 116), these groups are formed around “bureaucratic and hierarchical relations that declare who knows, what should be known, and what constitutes “good teaching” and “good schools.”

Figure 1

Characteristics of Knowledge Communities (Craig, 2007, p. 622-623)

In 2011, we initiated a longitudinal self-study into the workings of collaborative educator groups such as ours with the purpose of understanding the ways in which sustained collaboration contributes to the professional growth and development of group members and their continued improved group/individual practice (Curtis et al., 2012, 2013, 2016, 2018). The process of revisiting individual/collective experiences through reflection and critical professional discourse brought to light new aspects of previously known stories and, in some cases, uncovered stories never before shared (Craig et al., 2020a). These accounts ignited others’ reflections, too, as past members came forward to share their perspectives. Returning member, Annette, summed up her reaction to the group’s accounts of our collective history (Craig et al., 2020a) as “This is exactly the way it was.”

As we gathered at a local Mexican food restaurant, our group’s conversation shifted to the knowledge, skills, and practices acquired through our collaboration during the school reform era of the late 1990s (1998-2002) that are enacted in our current practice. We noted how the optimal experiences (Dewey, 1934) shared via Portfolio Group interactions have fueled other collaborations (Craig et al., 2020a) and shaped our individual practice. Reflecting on these ideas became the provocation of this self-study into the ways in which sustained interactions within teacher collaborative groups shape one’s practice and collaborative endeavors with other groups.

Aim/Objectives

Employing the “rear-view mirror” metaphor and taking a “reflective turn” back (Schön, 1991, p. 5), this self-study reflectively examined (Schön, 1983) the ways in which past reciprocal interactions of collaborative teacher/teacher educator/researcher groups shape/influence/inform our current practice. To advance our understanding of knowledge communities in improving our work with others, we wondered: What knowledge/skills/experiences have been gained as a result of our collaborative past interactions that are carried forward into our individual current practice and new educational landscapes?

Methods

This self-study employed narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) methods to explore the shaping effects of sustained collaborative group interaction on individual ongoing practice. Field texts spanning 25 years (stored at members’ homes) included meeting notes, past research texts, electronic communications, and individual reflective writings (Schön, 1983). Researchers’ personal journals and past group research texts (Curtis et al., 2012, 2013, 2016, 2018) provided a road map of sorts as we independently, then jointly, looked back at our collaborative journey to identify significant experiences. We then engaged in individual journaling around the identified experiences and continuous critical dialogue (Guilfoyle et al., 2004) through scheduled meetings and online collaborative writing, sharing stories/perspectives. Data were independently and collaboratively analyzed by group member researchers/authors and member checked by other non-author group members, intersecting narratives identified, and emergent themes determined. As self-study researchers, we hold firm to our “deep ethical obligation to reveal about others only those things they would want to make public” (Pinnegar & Murphy, 2019, p. 123 ). We drew on the authority of experience (Munby & Russell, 1994) and a mindful selection of professional exemplars that showed “how a practice works” (Lyons & LaBoskey, 2002, p. 6) to express transparency and promote trustworthiness.

Outcomes

Analysis of intersecting narratives identified four emergent themes: advancing the understanding of knowledge communities, optimal experience of collaboration, collaboration shaping future practice, and challenges of collaboration.

Advancing the Understanding of Knowledge Communities

The knowledge communities qualities (Craig, 2007) previously discussed (see Figure 1) anchor our discussion of how collaborative group interactions advance our understanding of knowledge communities, which has become a crucial part of our work with students and colleagues outside of the Portfolio Group. Annette’s reflection highlights how she applies Portfolio Group discussions around equity in education to other areas of her work.

As a person of color–for the first time in my educational career—the Portfolio Group afforded me the opportunity to sit in a group of diverse teachers who felt free to discuss ideas and that it was important to discuss culturally responsive teaching. I had a great deal of appreciation for the discussion of the fact that culture and the home environment play a role in how students of diverse backgrounds learn.

She continued, explaining,

Working with the Portfolio Group gave me the opportunity to see the work of other community liaisons while simultaneously doing my work in my school and community. The community liaison was a new position at that time within the school reform initiatives for our school district and other districts. I welcomed the opportunity to collaborate with others as we developed and shaped the work of a community liaison.

Gayle’s thoughts touch upon the shared ways of knowing found in knowledge communities.

We have learned by doing, reflecting, discussing, and co-constructing knowledge together. For some, our work contexts have not always provided spaces in which to share and discuss practice. The Portfolio Group has provided that space…resulting in constant learning and growth.

For Tim, the reciprocity found within our knowledge community strengthened his confidence.

The idea that I possess certain knowledge about teaching based upon my practice was particularly helpful during a period of uncertainty. The critical friendship of my Portfolio Group colleagues afforded me the safe place in which to present dilemmas centered within my new role.

Reflecting upon our group interactions showed the moral horizons that are evidenced in our collaboration. As Annette put it

I realized that my work had to encompass initiatives that would include the family and school working together for the common goal of successful student and parent learning.

Gayle added,

The trusting space of the group is a place to share our experiences and particular expertise, promoting a sense of narrative authority and empowerment among members.

Considering the ways in which ethics and moral horizons are reflected in the group’s shared experiences, Cheryl concluded,

Differences have never preempted our striving to be good people doing good work together. Portfolio Group members have always coalesced around this shared principle.

In her view,

There is an ongoing commitment to be “students of teaching” (Dewey, 1904, p. 215) in the Portfolio Group. If we accept the reality that teaching situations are not fixed, then that means there are limitless possibilities of what one can learn from students, but also from our milieu and changing landscapes.

Optimal Experience of Collaboration

Having experienced a fruitful collaboration like ours, we strive to work collaboratively with others. Department Chair, Michaelann, asked herself, “How am I modeling my long-standing values as a Portfolio Group member?” when working together with her ‘new’ team. Her first memo expressed the value she placed on collaboration and her understanding that we are stronger when we engage and work together.

COLLABORATION—Let's make this the word of the month—We need to work together and reflect that to the [university] community.

Cheryl shared,

Having seen growth within knowledge communities, I initiated regular team meetings with my doctoral students, loosely calling them a Research Team. Each year the team collaborates on a mutually agreed-upon project. Ju (pseudonym), a graduated doctoral student, described below what happened in the first two years.

Ju explained,

We did a performance narrative inquiry, which our Research Team of 10 graduate students presented. Seeing that every team member had unique contributions, Dr. Craig created a book chapter writing opportunity and each of us contributed to an edited volume. Now, each of us has a publication, as well as great relationships with each other.

Reflecting upon her return to the group, Annette wrote,

When I was first joined the Portfolio Group and now, the aspect of the Group’s knowledge community that promotes learning and professional growth for me is having the ability to gather with other professionals to collaborate, share our stories, and learn in a relaxed and trusting setting…This was influential in my decision to return to the group after 20 years.

On the optimal experience of our collaboration, Tim shared,

The very nature and longevity of the Portfolio Group and its research work have become self-sustaining. In other words, the more we work and research together, the more we wish to continue our collaboration.

In our final exemplar of the optimal experience of collaboration, we turn to a conversation between Gayle and Michaelann about their continued participation in the Portfolio Group.

Gayle: We each bring our particular expertise to the table…but it does not stop there. The knowledge and expertise shared contributes to the learning of the group and sometimes the “unlearning” (Vinz, 1997) of what we previously thought we knew…important for continued growth.

Michaelann: The Portfolio Group and my work with critical friendship has helped me to slow down in building relationships with new colleagues in order to ultimately go fast when working collaboratively.

Collaboration Shaping Our Future Practice

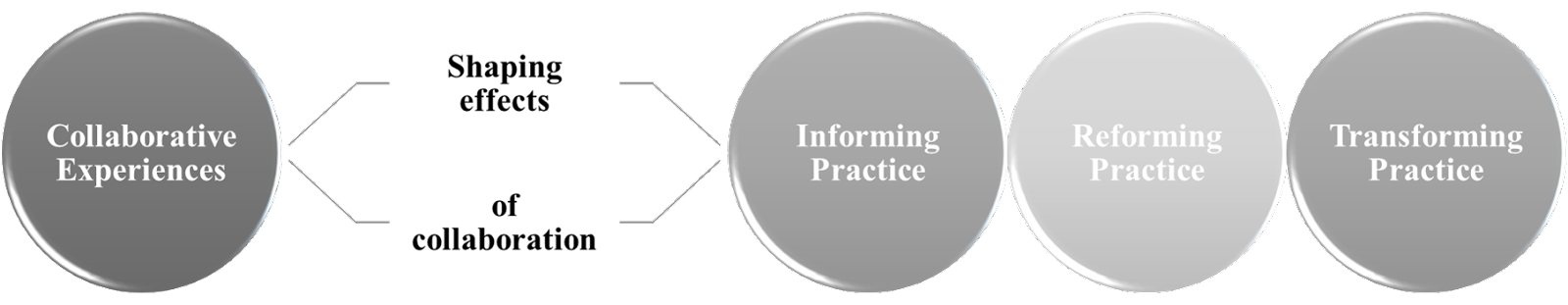

Coming together as experienced teachers, we each held a unique body of knowledge that contributed to the richness and depth of our conversations. Importantly, that knowledge did not remain stagnant but rather expanded and deepened as a result of collaboration. In examining the ways in which our Portfolio Group collaborative experiences shaped future practice, several sub-themes emerged, suggesting that collaboration sometimes informed our practice, and other times reformed it, and even transformed it (Tidwell et al., 2012; see also Curtis et al., 2013).

Figure 2

Framework for Shaping Effects of Collaboration Based on Tidwell et al., 2012

Building on Prior Knowledge

Our reflective writings highlighted ways in which the collaboration built on prior knowledge to inform practice. Annette shared,

For my yearly job performance review as a sales manager, I had to do a self-evaluation. I would write long, thorough narratives of my daily tasks to prove that I was doing an excellent job. I thought I knew exactly what I needed to do to document my work. As an educator working with the Portfolio Group and keeping a portfolio of data and artifacts of my school’s work, I really learned to do a better job of highlighting and illustrating change. The artifacts I gathered were tangible evidence of shifts taking place, which may have been imperceptible to others.

Similarly, Gayle wrote,

As a bilingual teacher, my knowledge and understanding of working with students from diverse backgrounds was deepened in the mid-1990s when the Portfolio Group participated in a university lecture series on working with diverse student populations. We all went away with something new to employ in the classroom. Discussing Ladson-Billings’ (1995) work on culturally relevant pedagogy together and later reading Gay’s (2000) book on culturally responsive teaching, was a validation that we were on the right track in our continued professional development and gave us further insights into working with diverse student populations.

On the evolution of the Faculty Academy (Curtis & Craig, 2020), Cheryl reflected,

The cross-school collaboration of the Portfolio Group became the prototype of the cross-institutional group called the Faculty Academy, with representatives from five regional and three affiliate universities.

Informing Future Practice Through Collaboration

Numerous exemplars selected from our reflective writings show the ways in which our collaboration has informed our practice. For instance, the knowledge and skills Mike carried forward facilitated his move to a new school. As he explained,

Although what I learned through implementing critical friendship at one campus was unappreciated, this same knowledge proved invaluable in my current school.

Similarly, knowledge gained through collaborative interactions has informed Tim’s practice. He explained,

A key piece of my own learning that I carry forward into my work with middle school colleagues and university teacher education students goes back to the concept of teachers’ narrative authority from Margaret Olson (1995) and the lessons learned from reading about the half-life and full-life of curriculum as Ted Aoki (1990) understands them.

Through her participation in the group, Cheryl gained new insights into the use of protocols. She shared,

I was often told as a formative researcher/evaluator how effectively the approach worked for teachers. It was not until I witnessed first-hand Art teachers assisting the Physical Education teachers at Eagle High School on how to use their storage space more optimally—through the use of a Critical Friends Group© Tuning Protocol—did the value of protocols become known to me in a deep, powerful way. This eventually prompted me to invite both a short version and a long version of a critical friendship course as part of the Collaborative for Innovation for Teacher Education at Texas A&M University with all Portfolio Group members teaching the synchronous or asynchronous courses when available.

For Annette, practices acquired during our early work together carried forward to new positions.

As the new District Lead Parent Trainer serving parents of students with disabilities, I draw heavily on my earlier experiences as a Community/Parent Liaison in developing processes and procedures for working with my new colleagues and parent groups. This includes using meeting protocols to promote the sharing ideas, analysis of curriculum/instruction outcomes, and reflection. I even carried forward the Portfolio Group’s practice of documenting our work through pictures, data, and artifacts.

She continued, explaining,

Fast forward, years later, my school district moved to an evaluation system that was mostly self-evaluation, with heavy emphasis on using artifacts to show how I accomplished my yearly goals. Because of my participation with the group, I came to know how to mindfully document my work still using some narratives, along with well documented data and artifacts.

Reforming Future Practice Through Collaboration

Reflecting on current practice, the capacity of collaboration to reform or change practice is illuminated. This is evidenced in Cheryl’s shifting perspective on the use of protocols.

At first, I thought the protocols for critical friendship used in the schools and in the portfolio creation process bounded teachers’ knowing too tightly, making things more about the instrumental use of the protocol than on what understanding teachers developed through the portfolio construction process. Then, I discovered that it all had to do with facilitation and whether the facilitator used the protocols as a guide or a harness. I witnessed Portfolio Group members engaged in very deft facilitation. The lightness of their touch won me over.

She continued,

This fine-tuned lesson I learned about facilitation has drifted over to my own teaching. Like other Portfolio Group members, I try to be light of touch in my instruction. The challenge I currently face is that I teach with guidance and facilitation in mind, while some younger students—with more recent experiences of the state accountability system and the constraints of pandemic asynchronous teaching—automatically expect to be harnessed. For them, being harnessed is the norm. Anything else does not equate to teaching as they know it. We are currently negotiating the in-between space. This goes to show that how one teaches—and how one facilitates—can never be predetermined. It is always in negotiation/in response to learners and the milieu in which teaching and learning fuse.

For Michaelann, the collaboration shifted her mindful presence while working with others.

The Portfolio Group was the place where I learned how to listen to authentic feedback, how to present the ‘work/data’ of a school beyond the test scores, how to represent learning from multiple points of view, and most of all how to be part of a group with distributive leadership. These skills are being used and refined in my current practice as the new department chair.

She continued, explaining,

I spent my first interactions with each faculty member listening to their background, their experiences with teaching and learning, and views of the department. Like Margaret Olson (1995) says, it is important for us to make spaces in our classrooms to tell and hear stories of experience in education…The same applies to our work and interactions with colleagues.

Transforming Future Practice Through Collaboration

Through analysis of our reflective writings, many examples showed how practice was reconstructed as a result of group collaboration. For Mike, this was evidenced in his shift in reflective practice.

As a middle school science teacher in an urban setting, at first I found the research perspectives of narrative inquiry and self-study contrary to the quantitative research I experienced in my undergraduate and graduate research. However, over time I began to appreciate this new perspective and its foundation in reflective practice.

Annette explained,

Working with students of different abilities I have come to know that we have to meet our students where they are. I like to look at their abilities instead of disabilities. I know that I have to take what they have and scaffold and differentiate what I am teaching in order to bring out the best of what they have to help them be successful.

Annette added,

As a result of working with the Portfolio Group, in a twenty-year span I can say that I am still working on the important goal of breaking down barriers to positive relationships between families and schools.

Reflecting on these ideas, Gayle shared,

Whereas previously I would have been reluctant to join a faculty group in higher education for fear of an environment filled with complaints and egos jockeying for position, my experiences with the Portfolio Group made me eager to participate in the Faculty Academy when I moved into higher education and to mentor Las Chicas Críticas (Cooper et al., 2020) in self-study research.

Challenges of Collaboration

Our joint experiences have shown us that people working together provide no guarantee that individuals are actually collaborating or co-constructing knowledge and that individual engagement occasionally “waxes-and-wanes” within groups. Nor is there an assurance that members' interactions will constitute an optimal experience. People enter professional groups with varying degrees of engagement and assign different values for reflection and their role in the improvement of practice. Intertwined in each of these considerations is personal choice and responsibility. This suggests to us that a requisite for achieving individual optimal experience within groups is individual responsibility for contributing to the community’s shared vision, expressing one’s own agentic voice, and advancing the group's agenda. These are challenging considerations we carry into our work with other groups. For example, Michaelann takes these ideas into consideration in working in her new context.

An area that I am still struggling with in my new venue is distributive leadership. I am struggling because this is not something that you can impose or command. Reflecting back on the journey of the Portfolio Group, it took years for the group to move from a singular leader to a non-hierarchical leadership model. This is knowledge that comforts me, yet like most of us, I want the process to happen faster. I want the other professors to grab ideas and run with them. I want them to work the way I work…but that is not the norm for most. I need to realize this and adjust my perceptions, not try to adjust others.

To this, Cheryl added,

The members of the Portfolio Group have an unspoken understanding that practical knowledge is provisional in nature (always changing in and of itself) and highly dependent on context. They are able to live in a space of inconclusivity, as Stefinee Pinnegar and Marylynn Hamilton (2012) term it. Many people would not feel comfortable with this lack of certainty.

Discussion

The stories shared illustrate how looking into the rear-view mirror to study our optimal past collaborative experiences gives insight into the ways such experiences shape current and ongoing individual practice. They show through exemplars the various characteristics of knowledge communities (Craig, 2007) that differentiate knowledge communities from other forms of communities of learning. They also highlight the ways in which the “safe, storytelling places” (Olson & Craig, 2001, p. 670) of knowledge communities encourage the exchange of ideas and reflection on individual practices, leading to reciprocal learning and teacher professional growth.

An implication/consideration to be taken away from this study is that looking in the rear-view mirror at previous experiences helps us to better understand the many theoretical, practical, and experiential factors that have shaped our teaching, our learning, and our stance as teachers/teacher educators/researchers. The professional growth and generative spaces of teacher collaborative groups are deeply connected to the satisfaction found within those groups and the collaborative work they engage in. On the whole, we have discovered that the more people involved in the groups in question, as well as the differing contexts in which they were formed, make for even more complex and nuanced self-studies.

This work makes an especially important contribution, not only because of the varying positions and subject matters the researchers represent but also because of the length of time the group has sustained itself. Also, the different iterations of knowledge communities we have shared (i.e., faculty department, Research Team, Faculty Academy, parent groups, Las Chicas Críticas) show how the characteristics of knowledge communities have expanded specifically to other named groups and into the lifeblood of the field more generally.

Our past experiences and knowledge inform/reform/transform our daily practice pushing us to continually seek those optimal experiences with colleagues in our new professional landscapes. The priceless value of a rear-view mirror while moving forward holds the same limitless value to ourselves and our peers and most importantly to the professional scholarly landscape.

References

Aoki, T. (1990). The half life of curriculum and pedagogy. One World, 27(2), 1-10.

Clandinin, D. J. & Connelly, F. M. (1994). Personal experience methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 413-427). Sage.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass.

Cooper, J. M., Gauna, L. M., Beaudry, C. E., & Curtis, G. A. (2020). Sustaining critical practice in contested spaces: Teacher educators resist narrowing definitions of curriculum. In Craig, C. J., Turchi, L., & McDonald, D. M. (Eds.) Cross-disciplinary, cross-institutional collaboration in teacher education: Cases of learning while leading (pp. 337-349). Palgrave Macmillan.

Craig, C. J. (2007). Illuminating qualities of knowledge communities in a portfolio-making context. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(6), 617-636.

Craig, C. J., Curtis, G. A., Kelley, M., Martindell, P. T., & Perez, M. M. (2020a). Knowledge communities in teacher education: Sustaining collaborative work. Palgrave Macmillan.

Craig, J., & Olson, M. (2002). The development of teachers’ narrative authority in knowledge communities: A narrative approach to teacher learning. In N. Lyons & V. LaBoskey (Eds.) Narrative inquiry in practice: Advancing the knowledge of teaching (pp. 115-129). Teachers College Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. HarperCollins.

Curry, M. (2008). Critical friends groups: The possibilities and limitations embedded in teacher professional communities aimed at instructional improvement and school reform. Teachers College Record, 110(4), 733-774.

Curtis, G. A., & Craig, C. J. (2020). Faculty Academy: A new version of an established concept of collaboration. In C. J. Craig, L. B. Turchi, & D. McDonald (Eds.) (2020). Cross-disciplinary, cross-institutional collaboration in teacher education: Cases of learning while leading (pp. 9-24). Palgrave Macmillan.

Curtis, G. A., Craig, C. J., Kelley, M. (2016). Sustaining self and others in the teaching profession: A group self-study. In D. Garbett and A. Ovens (Eds.) Enacting self as methodology for professional inquiry (pp. 133-140). Self-study of Teacher Education Practices.

Curtis, G. A., Craig, C. J., Reid, D., Kelley, M., Glamser, M. Martindell, P. T., & Gray, P. (2012). Braided journeys: A self-study of sustained teacher collaborations. In J.R. Young, L. B. Erickson, S. Pinnegar (Eds.) Extending inquiry communities: Illuminating teacher education through self-study (pp. 82-85). Brigham Young University.

Curtis, G. A., Kelley, M., Reid, D. Craig, C. J., Martindell, P. T., & Perez, M. M. (2018). Jumping the Dragon Gate: Experience, contexts, career pathways, and professional identity. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for knowing pedagogy (pp. 51-58). Herstmonceux, UK: S-Step.

Curtis, G. A., Reid, D., Craig, C. J., Kelley, M., & Martindell, P. T. (2013). Braided lives: Multiple ways of knowing flowing in and out of professional lives. Studying Teacher Education, 9(2), 175–186.

Dewey, J. (1904). The relation of theory to practice in education. In C. A. McMurray (Ed.) The third NSSE yearbook. University of Chicago.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Capricorn Books.

DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (1998). Professional learning communities at work: Best practices for enhancing student achievement. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Eisner, E. W. (1997). The promise and perils of alternative forms of data representation. Educational Researcher, 26(6), 4-10.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Guilfoyle, K., Hamilton, M. L., Pinnegar, S., & Placier, P. (2004). The epistemological dimensions and dynamics of professional dialogue in self-study. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 1109–1167). Springer.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159–165.

Lyons, N. (1998a). Reflection in teaching: Can it be developmental? A portfolio perspective. Teacher Education Quarterly, 25(1), 115-127.

Lyons, N. (1998b). With portfolio in hand: Validating the new teacher professionalism. Teachers College Press.

Lyons, N. (Ed.) (2010). Handbook of reflection and reflective inquiry: Mapping a way of knowing for professional reflective inquiry. Springer.

Lyons, N., & LaBoskey, V. K. (Eds.) (2002). Narrative inquiry in practice: Advancing the knowledge of teaching. Teachers College Press.

Munby, H., & Russell, T. (1994). The authority of experience in learning to teach: Message from a physics methods classroom. Journal of Teacher Education, 25(2), 89–95.

Olson, M. R. (1995). Conceptualizing narrative authority: Implications for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(2), 119-135.

Olson, M. R., & Craig, C. J. (2001). Opportunities and challenges in the development of teachers’ knowledge: The development of narrative authority through knowledge communities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(6), 667-684.

Pinnegar, S., & Hamilton, M. L. (2012). Openness and inconclusivity in interpretation in narrative inquiry: Dimensions of the social/personal. In E. Chan, D. Keyes, & V. Ross (Eds.) Narrative inquirers in the midst of meaning-making: Interpretive acts of teacher educators (pp.1-22). Emerald.

Pinnegar, S., & Murphy, M. S. (2019). Ethical dilemmas of a self-study researcher: A narrative analysis of ethics in the process of S-STEP research. In R. Brandenburg & S. McDonough (Eds.) Ethics, self-study research methodology and teacher education (pp. 117-130). Springer.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (Ed.) (1991). The reflective turn: Case studies of reflection in and education practice. Teachers College Press.

Tidwell, D., Farrell, J., Brown, N., Taylor, M., Coia, L., Abihanna, R., Abrams, L., Dacey, C., Dauplaise, J., & Strom, K (2012). Presidential session: The transformative nature of self-study. In J. Young, L. Erickson, & S. Pinnegar (Eds.), Extending inquiry communities: Illuminating teacher education through self study. (Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Self-study of Teacher Education Practices, pp. 15–16). Brigham Young University.

Vinz, R. (1997). Capturing a moving form: ‘Becoming’ as teachers. English Education, 29(2), 137-146.