Beyond Critical Reflection

Breaking Old Habits and Shifting Pedagogical Values

Introduction

Our friendship began over a decade ago when we met in a doctoral program studying the theory and practice of teaching and learning. We connected over our past experiences as educators of young children and our emerging perspectives on the field of education. Upon our completion of the program, we both began our careers in tenure-track positions at two different public universities in the northeast of the United States. We found ourselves continuing to connect about our experiences as new teacher educators, with a shared desire to engage intellectually, with a trusted friend, about our teaching practices. Since then, we have continued our collaborative reflections and engaged in a collaborative self-study (Hamilton & Pinnegar, 2009) and critical friendship (Schuck & Russell, 2005) for the past five years. In this work, we designed a framework for our critically reflective teaching practice in which we ask ourselves and other educators to consider who and where they teach, what and how they teach, and why they make those choices (Buchanan & Clark, 2018, 2021). We have found that iteratively engaging with this framework has shifted our own practice, as we hone our pedagogical commitments in relation to the communities in which we operate.

During the past two years, we have used these questions to examine our own emotional and pedagogical challenges and responses to teaching during a global pandemic. This contextual reality caused us to break with one of the ways we have previously communicated, through prose journal posts in a shared document. In order to navigate the realities of teaching during the pandemic, we found ourselves moving beyond the written form towards using creative means (painting, fiber arts, and poetry) as a way to make sense of our experiences, aiming to understand and heal (Clark & Buchanan, 2021). This shared process of creative sensemaking also revealed the value of collective engagement, particularly in attending to the isolation of teaching during the pandemic, but has also more broadly reshaped our understanding of what it means to engage in the work of teaching.

This process was generative and has led us to examine how we may better bring these acts of care, collectivism, creativity, and critical self-reflection into our learning communities with preservice teachers. In particular, we recognize that the institutions in which we exist privilege individualism; judgment; competition; and linear, written expression- often denying preservice teachers authentic opportunities to engage collectively or creatively and deemphasizing care and critical reflection.

Literature Review

Over the past ten years, we have discovered how our critical friendship and teaching practices have been grounded in a set of themes that have emerged from our discussions, artwork, writings, and other creative acts. Utilizing the methodology of self-study (Laboskey, 2004), which proposes a process of research on one’s own teaching practices by asking questions that encourage thoughtful and methodical discussion and reflection, four themes have emerged in our work: critical reflection, care, collectivism, and creativity.

Our collaborative self-study has taken multiple forms over the years, including both written and creative expression, which has encouraged both vulnerability and connection (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2016; Clark & Buchanan, 2021). Moreover, our work has prioritized a dialogic form of critical reflection, the first of our emerging themes, which emphasizes the importance of reflection in the service of social justice, always considering how power operates at multiple levels, including society, schools, classrooms, and learning relationships (Buchanan & Clark, 2018; Clark & Buchanan, 2020).

The second theme emerging from our work is the concept of care. Nel Noddings (2013) framed the concept of care as a relational, dialogic approach to learning and interacting with one another, going beyond a one-way transaction. Her work describes how the act of caring is based on a reciprocal connection, where interaction, exchange, and understanding are required from all participants. Rabin (2008) applies an ethic of care to her work with novice teachers in a teacher education program by examining the opportunities that they have to engage and understand the ethical components of care when teaching. Rabin aligns care with Lev Vygotsky’s learning theory of constructivism, where interactions drive meaning-making based on social and cultural understandings. Shawn Ginwright’s (2022) work directly connects this ethic to acts and understandings of justice in education.

“...care is deeply rooted in our notions of justice….Care is our collective capacity to express concern and empathy for one another. It requires that we act in ways that protect, defend, and advance the dignity of all human beings, animals and the environment. This gets at the core of what justice is about: the act of caring for the well-being and dignity of others.” (Ginwright, 2022, p.121)

This notion of care is, therefore, both dialogic, emerging across differences and understandings, and collective, as it requires that we move beyond our individual acts and towards our interactions with one another. Collectivism, our third theme, is defined by the relationships and communities that hold space for vulnerability, curiosity, and care as we connect with a very specific goal: supporting one another as a learning community. Education tends to emphasize individualism (Labaree, 1997), repeating patterns that exist in our capitalist economy (Anyon, 2011). Research has demonstrated that when teachers are engaged in collective work, it can lead to teacher remoralization and liberation in pedagogy (Santoro, 2018; Buchanan et al., 2020; Clark, 2018). We believe that a shift towards collectivism can support teacher well-being and retention, but also better serve social justice goals in education, by emphasizing the relational aspects of teaching and learning (between teachers and their colleagues as well as teachers and their students) instead of competition, accountability, and hierarchy.

Creativity, our fourth and final theme, has been the most recent emergence from our work. Four months into the COVID-19 global pandemic, we found ourselves beginning to move away from written journal entries towards more artistic and creative expressions to help communicate our feelings and responses to teaching during these new challenging times (Clark & Buchanan, 2021). We found, as others have, that creative means of expression in pedagogical reflection can be both generative, innovative, and healing (Pithouse-Morgan & Van Laren, 2012; Tan & Ng, 2021; Evans, Ka’opua & Freese, 2015).

Methodology

Our ongoing practice of collaborative self-study (Laboskey, 2004), has involved a co-authored online journal, including both written and creative entries. These entries focus on our teaching practices, identities, and interactions with institutions of education (Buchanan & Clark, 2018; Clark & Buchanan, 2021). Our creative dialogues helped us deepen our inquiries, reinventing our methodology and allowing for more joy, wonder, and improvisation (Pithouse-Morgan et al., 2016). Recently we have shifted from examining our personal interactions in teaching and begun to reflect on a different component: our course assignments. This particular paper reports on an examination of how the themes we identified above operate in a single assignment designed by Rebecca and an analysis that consists of two phases. We are the participants in this research, with Rebecca as a lead, Maggie operating primarily as a critical friend (Schuck & Russell, 2005), as well as preservice teachers in Rebecca’s Fall 2021 Multicultural Education course. The first phase was an examination of the assignment design, exploring the opportunities for creativity, care, collectivism, and critical reflection within one of Rebecca’s assignments.

The final assignment for the Multicultural Education course that Rebecca teaches is an advocacy project. The students select a topic broadly related to culture, power, and schooling; conduct research on their topic; write a paper based on their research that advocates for a particular position; and then communicate what they have learned in some other, more creative format, called an artifact. This assignment is part of a course that is required for all undergraduate students working towards teacher licensure at Rebecca’s institution.

Rebecca began the analysis process through journaling about her assignment design with particular attention to the four themes and how they operate within the assignment using the following guiding questions as prompts:

- Creativity: In what ways does the assignment offer opportunities for students to demonstrate their meaning-making in alternative ways - beyond the written form?

- Collectivism: In what ways does the assignment give space for students to think beyond the individual process of learning and teaching and shift towards a collective perspective (ie., dialogic, societal, and global)?

- Care: In what ways does the assignment offer flexibility and ways for both us (as teacher educators) to demonstrate care to our students and for them (as emerging educators) to reflect on care within their own pedagogies?

- Critical Reflection: In what ways does the assignment encourage students to examine their sociopolitical location in society and the interplay of power and privilege in learning, schooling, and teaching?

Maggie, then, operated as a critical friend, using the comment function to respond to the journal. We also met afterward to discuss our examination synchronously over the phone.

During the second phase of the study, 25 individual artifacts from this assignment from Rebecca’s course, were collected and analyzed for evidence of the same four themes. An Institutional Review Board approved the collection of these artifacts and preservice teachers had the option to decline the inclusion of their artifacts in the dataset. Each artifact was downloaded and an analytical table was created with columns for all themes. The table included the artifact title, what topic it addressed, and notes on the ways in which the four themes were or were not made manifest in the artifact design. An example from the analytical chart is included below. Rebecca completed the first round of analysis. After completing the analytical chart, Rebecca wrote analytical memos for patterns she noted across the different artifacts. Acting as a critical friend, Maggie then reviewed all 25 artifacts, the analytical table, and the analytical memos, responding with comments in the margin. This process involved us returning to the assignment analysis and design, reconsidering which themes were privileged, why, and how.

Table 1

Analysis Table Excerpt

| Artifact | Topic | Creativity | Care | Collectivism | Criticality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxie-Sea | Mental Health | Tons of evidence of creativity. Obviously, this PST is a skilled artist, but the weaving together of ocean facts with the images to communicate the emotions of the protagonist is astonishing. | This PST is thinking about how to provide supportive texts for students. | Little evidence explicitly in this artifact. | While there is little evidence explicitly in the artifact, the centralizing of mental health over content is implicitly critical. |

Outcomes

The four themes we are exploring - creativity, collectivism, care, and critical reflection - emerged from our previous collaborative self-studies. This particular self-study allowed us to focus on how we enacted these principles through a specific slice of our teaching: the course assignment. The findings are organized around these four themes, explicating our learnings during both phases of analysis.

Creativity

Analysis of the assignment itself revealed that it not only offered, but required students to make sense of their topic and communicate their learnings in creative ways that are not traditionally academic. This requirement created tension for some students, who have been so well schooled, that asking them to engage creatively felt risky, because of the vulnerability it required.

However, this requirement also resulted in a wealth of creative approaches utilized by preservice teachers as they developed their artifacts. The example below comes from a preservice teacher whose final project focused on dress codes. She began the project with an interest in how sexism is embedded in dress codes, but through her research (guided in part by suggestions from Rebecca) came to learn about how dress codes also perpetuate racism and heteronormativity. This is all represented in an original collage-style painting she created for the project.

Figure 1

Dress Codes Collage

Analysis of course assignments also opened up new ways of thinking about creativity for Rebecca as evidenced in this excerpt from a collaborative memo:

I’ve been thinking about the multiple kinds of creativity that are being explored in these artifacts. I had originally conceived of creativity as something to do with fine arts, such as painting, drawing, or filmmaking. One of the pieces that is coming out of this analysis is the different kinds of creativity. How creativity can be displayed even in text-based work. And how students use different tools to support their creativity. Many of them make flyers or infographics to display their information in visually appealing ways, but they use digital tools to support their designs.

Rebecca also reflected on the ways that processing material through creative means can feel intimidating to students. Multiple students noted that they struggled with how skilled some of their peers were with particular artistic mediums. More than one student has introduced their artifact with the disclaimer “I am not an artist.” This self-study demanded that as teacher educators we consider the tension between pushing students outside of their comfort zone with assignments like this one - particularly when neither of us is an art educator - and the value of sense-making through non-linear, multimodal means.

Collectivism

In the first phase of analysis, collectivism was one of the areas that seemed most lacking within the assignment design. In her analytical memo, Rebecca wrote:

The assignment is completed individually, because it also serves as a key assessment that our program reports data on for accreditation, so I feel compelled to collect individual data for each student. This, in itself, works against our goals of collectivism, and roots teacher development in the individualistic framework. However, the goal of the assignment is that it is shared beyond the walls of the classroom. Sometimes students create websites, infographics, pieces of art, and videos that they have shared on personal social media accounts, with their peers, and with practicing educators.

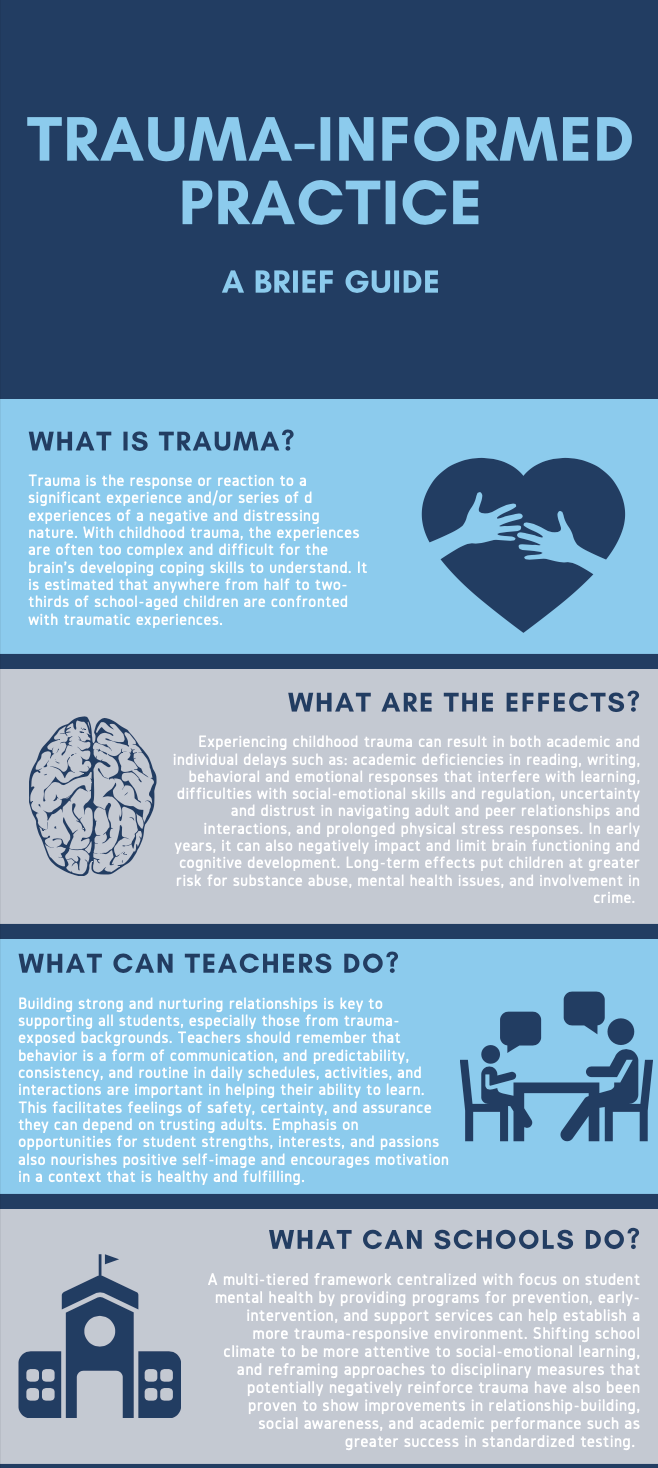

Not surprisingly, in the artifact analysis, we found little explicit attention to teaching as a collective endeavor. In one preservice teacher’s project on trauma-informed instruction, she explicitly calls attention to the need for multi-tiered systems of support beyond classrooms, which indicates the collective work involved in creating holistic, student-centered learning environments. This preservice teacher was particularly concerned about how useful and clear the information was in her infographic because she intended to use it at the school where she was working as a paraprofessional.

Figure 2

Trauma-informed Practice Infographic

However, our analysis also revealed how preservice teacher advocacy often involved a call to action on the part of educators, demonstrating an implicit recognition that they can not engage in transformative educational practice alone. Similarly, through prompting from Maggie, Rebecca realized that the barriers presented in accreditation requirements weren't necessarily as rigid as she had originally perceived. We began to consider ways to have preservice teachers work collaboratively to research similar topics, write group papers, and create joint artifacts.

Care

Phase one analysis of the assignment design caused Rebecca to reflect on care at two levels: how does she enact care in her support of students as they engage with the assignment as well as what ways the assignment asks preservice teachers to consider integrating care into their own educational philosophy.

I guide students through the process in stages, offering feedback along the way and regular support. I also allow them to shift, redesign, and adjust their plans as necessary. I hope that this, implicitly, communicates care as I engage in humanizing pedagogies. However, this is not something I have typically made explicit. I do think that because they are often advocating for greater attention to the needs of historically marginalized populations through their work, they are able to explore the lack of care within traditional educational structures, and consider how to be more care-full as educators.

Phase two analysis revealed that care was an implicit component of preservice teachers’ artifacts. They were typically advocating for more attention to the needs of marginalized students. This advocacy was often focused on ways to create more humanizing educational spaces, often regarding relationships between teachers and students. Many of the projects focused explicitly on the mental health needs of students, such as the project below.

Figure 3

Anxie-Sea Picture Book

In this artifact, a preservice teacher has created a picture book that examines the anxiety experienced by the adolescent protagonist by weaving in her experience at a new school with facts about the ocean. This preservice teacher adeptly, and creatively, explored aspects that are often overlooked in PK-12 schools, demonstrating both the need to attend to the mental health of students as well as a means through which to do so.

Critical Reflection

Phase one analysis illustrated the centrality of critical reflection to the entire course design. Given our previous self-study work that has emphasized critical reflection, this was not necessarily a surprise, as we have developed particular methods for asking students to critically examine their sociopolitical location and consider the relational implications of that analysis in their developing identities as educators. In reflection on this assignment in particular, Rebecca wrote, “This assignment asks them to go beyond personal reflection to consider what needs to change and how it might occur, as they make choices about how to represent their learnings and communicate them with a broader audience.”

Phase two analysis demonstrated that, like care, much of the criticality was implicit rather than explicit. However, creating artifacts that drew from their previous critical reflection and demonstrated a call to action, reveals how preservice teachers were putting that criticality to use. In one artifact, a short video that examines myths about people who experience poverty - and advocates for a universal basic income, the preservice teacher is explicitly critical as she debunks the stereotypes around poverty. This preservice teacher uses stock images, personal photos, and video-editing skills to unpack the often-unspoken biases regarding people in poverty and advocate for universal basic income, a concept she learned about in class.

Figure 4

Screenshot of Film About Poverty and Stereotypes

Acting as a critical friend when reviewing the artifacts, Maggie noted:

I feel like both you and I have the criticality…embedded in our pedagogies, the content, the assignments - by the nature of the topics that we choose. Criticality is a central tenet to who we are, our identities as humanizing pedagogues. However, the other three categories (creativity, care, and collectivism) seem to be harder to achieve... (or do they?)...I have to remember to offer multiple methods for expression. I have to break my habits in order to centralize creativity, care, and collectivism. I wonder how much that has to do with our own education... and our students' education. So many of them have expressed that they'd prefer to just write papers as individuals.... they don't want group work, they don't want to have to do some creative expression. [Our schools] train our students to think individually, express themselves through writing, and learn in environments that aren't always caring. By bringing forth these tenets, we are asking them to get out those traditional pathways of learning and assessment.

This quote demonstrates the power of collaborative self-study for examining our experiences and the feedback we receive from students critically. It also highlights the challenges we face as teacher educators who seek to disrupt traditional, institutionalized patterns of learning and teaching.

Discussion

On Student Perspectives and Experiences

In this critical and collaborative self-study, we aimed to further explore a series of themes that had emerged in our prior work: care, collectivism, creativity, and critical reflection. For this project, we wanted to focus on a specific component of our teaching: the course assignment in Rebecca’s undergraduate education course. In the design of this study, we aimed to create a systematic, purposeful review of the assignment and how it was enacted by the students in this course. We found that for this group of students, engaging with these concepts in their learning process of completing this assignment, was a challenge for some and welcomed by others. As seen in the artifacts shared in this paper, some students took the opportunity to design and create advocacy projects and artifacts that manifested care and collectivism in teaching and learning. However, other students were challenged by this assignment. In our analysis, Rebecca described feeling like it was a “mixed bag” of student responses at the end of the semester. Maggie connected this back to her own assignments, which ask for creative expressions and collaborative approaches, and how students have multiple “hesitancies” when sharing their thinking and learning this way. Despite these challenges, we also discovered that this assignment, and others like it, do offer students opportunities to reflect in innovative ways that they might not have otherwise utilized in their teacher education coursework. These opportunities allow students to share their sensemaking in non-linear, non-written, open-ended, and action-focused ways. For a project about advocacy, we found that creativity can be the lynchpin for preservice teachers to feel comfortable taking action because the work has a more personal connection. At the conclusion of the assignment, the students also shared their work with one another during class, describing and discussing their process in the act of creating it, which promoted collective inquiry, sensemaking, and vulnerability.

Our Own Perspectives and Experiences

As is demonstrated in the quote above from the critical reflection section, this process provided opportunities for us to pause and think anew about our course assignment design, implementation, and assessment. In our future reflections, we plan to continue to ask ourselves: How can we better align our course assignments with our pedagogical beliefs about teaching and learning? How can we move away from a product focus (assignment/rubric/collection/grading) to a process-focused learning experience? How can we further inject opportunities for our students to engage in artistic and creative expression, ground their work in concepts of care, and connect it to a community, beyond their own learning and teaching processes? Despite a years-long focus on critical reflection, we found that diving into a particular assignment revealed blind-spots, such as the assumptions around accreditation demands. And collaborative reflection provided opportunities to imagine new possibilities and more effectively navigate (perceived) institutional barriers.

Significance in the Action

Our findings demonstrate the generative capacity of reframing teacher education and considering - at the micro level - what this means for preservice teacher experience. We found that prioritizing these four themes: creativity, care, collectivism, and critical reflection, supported our preservice teachers in thinking differently and even becoming different, because of the shifts in not only content but also process. Requiring multi-modal expression, and sharing that learning with others, also encouraged preservice teachers to consider how they might apply similar principles in their future work with PK-12 students - extending the action beyond the teacher education coursework.

For teacher educators who are interested in resisting traditional educational practices, this paper offers an exploration of how to go beyond the critique of critical reflection into the action. Praxis requires both reflection and action (Freire, 1970), and this particular analysis demonstrates how an emphasis on action and advocacy can operate both within a preservice teacher education course and beyond, demonstrating a method for navigating institutional barriers, and encouraging preservice teachers to share their advocacy more broadly.

References

Anyon, J. (2011). Marx and education. Routledge.

Buchanan, R. Mills, T., & Mooney, E. (2020). Working across time and space: Developing a framework for teacher leadership throughout a teaching career. Professional Development in Education, 46(4), 1-13.

Buchanan. R. & Clark, M. (2018). At the top of every syllabus: Examining & becoming (critical) reflective practitioners. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for knowing pedagogy. Herstmonceux, UK: S-STEP, ISBN: 978-0-473-35893-8.

Buchanan, R., & Clark, M. (2021). Developing (as) critically reflective practitioners: Linking pre-service teacher and teacher educator development. In L. Shagrir & S. Bar-Tal (Eds). Exploring Professional Development Opportunities for Teacher Educators (35-52). Routledge.

Clark, M. (2018). Edges and boundaries: Finding community and innovation as an early childhood educator. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1-10. DOI: 10.1007/s10643-018-0904-z

Clark, M. & Buchanan, R. (2020). Weaving Our Strengths: Sustaining Practices & Critical Reflections in Teacher Education. In C. Edge, A. Cameron-Standerford, & B. Bergh (Eds.), Textiles and Tapestries: Self-Study for Envisioning New Ways of Knowing. EdTech Books. Retrieved on August 29 2022 from: https://edtechbooks.org/textiles_tapestries_self_study/chapter_15

Clark, M. & Buchanan, R. (2021). Examined lives: 10 reflections on our pandemic pedagogies. In K.A. Lewis, K. Banda, M. Briseno, E.J. Weber (Eds.) The Kaleidoscope of Lived Curricula: Learning Through a Confluence of Crises (13th Annual Curriculum & Pedagogy Group, 2021 Edited Collection). Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Evans, D.P., Ka’Opua, H., & Freese, A. R. (2015). Work gloves and a green sea turtle: Collaborating on a dialogic process of professional learning. In K. Pithouse-Morgan & A.P. Samaras (Eds.), Polyvocal professional learning through self-study (pp. 21-37). Sense.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Ginwright, S. (2022). The Four Pivots: Reimagining Justice, Reimagining Ourselves. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Hamilton, M. L., & Pinnegar, S. E. (2009). Self-study of practice as a genre of qualitative research: Theory, methodology, and practice. Springer.

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public goods, private goods: The American struggle over educational goals. American educational research journal, 34(1), 39-81.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M.L. Hamilton, V. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817–869). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Noddings, N. (2013). Caring: A relational approach to ethics and moral education. Univ of California Press.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., van Laren, L. (2012). Towards academic generativity: Working collaboratively with visual artefacts for self-study and social change. South African Journal of Education, 32(4), 416-427.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Coia, L., Taylor, M., & Samaras, A. P. (2016). Exploring methodological inventiveness through collective artful self-study research. LEARNing Landscapes, 9(2), 443-460.

Rabin, C. (2008). Constructing an ethic of care in teacher education: Narrative as pedagogy toward care. The Constructivist, 19(1).

Santoro, D. A. (2018). Is it burnout? Or demoralization. Educational Leadership, 75(9), 10-15.

Schuck, S., & Russell, T. (2005). Self-study, critical friendship, and the complexities of teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 1(2), 107-121.

Tan, C., & Ng, C. S. (2021). Cultivating creativity in a high-performing education system: The example of Singapore. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 18(3), 253-272.